Better future for subsistence farmers

EMPOWERING NEPALI FARMERS

LIFE AS A subsistence farmer in the remote, mountainous communities of Nepal comes with unique challenges, such as seed shortages, sloped fields, and labour deficits. That’s why University of Guelph researchers have found a way to provide the necessary scientific knowledge, seed stocks, and inexpensive tools to improve these issues among the world’s poorest and most remote agricultural communities.

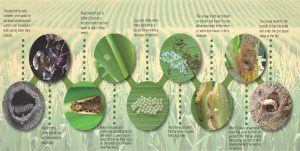

Professor Manish Raizada and his team at the Department of Plant Agriculture, along with partners in Nepal, have created sustainable agriculture kits (SAKs). SAKs consist of seed kits, tools, and a book of practices that contain captioned illustrations of effective sustainable practices and how to use components within the kit.

These books play a huge role in the SAK project, as many subsistence farmers, especially women, are illiterate. Researchers were inspired by historical efforts in North America to increase the agriculture industry. In the 1900s, North American agriculture flourished through public agricultural extension programs that applied scientific knowledge to improve seeds and practices. Extension officers worked directly with farmers to improve agriculture and the SAK picture books were designed to play a similar role but at a smaller scale and much lower cost.

One agricultural practice that’s proved to be a huge breakthrough is vertical farming, as Nepali farmers rely on terraces to cultivate steep mountain slopes. Vertical land, which makes up 30 to 50 per cent of the area, was previously left uncultivated. Growing crops on those surfaces provides income and enriches the soil, according to the researchers.

Within the menu of options, there are seed and propagation kits consisting of packages of vegetables, legumes, and root crops. They are all Nepalese varieties developed in partnership with Anamolbiù, a Nepali seed company that procures and markets the SAKs through village level vendors, radio, and print media.

“The intent is not to displace any indigenous varieties — it’s to meet critical shortages in seeds or disease-free seeds, based on varieties already approved within Nepal,” says Raizada. “We offer a regional menu, in this case for Nepal, from which a farming household can choose one or multiple products or practices. Every household has different needs, and different purchasing and practicing abilities.”

Farmers were surveyed before the project to determine which varieties they’d like to grow. But it’s the simple tools, such as corn shellers, garden gloves, and weed rakes that have made the biggest impact on the farmers’ lives.

For example, traditional practices, such as removing corn kernels by hand and then beating them in bags with a stick to make flour, are hard on the body and time consuming. With a corn sheller, 17.5 kilograms of kernels can be shelled in 30 minutes, as opposed to two-and-a-half hours by hand. A pair of $1 gloves means thorny weeds and crops can be handled quickly and painlessly.

Raizada says saving time is extremely important in Nepal, where there is a severe labour deficit.

“A lot of tools were designed to reduce female drudgery. In Nepal, men often leave to become migrant workers overseas,” he says. “This project is reducing the labour requirement for women who remain on the farm, so they can maximize their productivity.”

Many of the Nepali SAKs practices and products transfer easily to subsistence agriculture in other countries that struggle with political, resource, and geographical complications. The SAK team has already created five different versions of the picture book, customized to different subsistence farming regions and are looking to reach farmers in sub-Saharan Africa in the near future.

This project was funded by the Canadian International Food Security Research Fund program, jointly funded by the International Development Research Centre and Global Affairs Canada. •