The WBC problem

AVOIDING THE DAMAGE OF 2016

LAST SEASON WAS officially the worst year on record in Ontario for Western bean cutworm (WBC) feeding damage. What’s even more troubling is that cutworm feeding damage was also a major contributor to high deoxynivalenol (DON) (vomitoxin) test levels.

Here’s what happened. After scouting their fields towards the end of July, quite a few farmers either didn’t see cutworm egg masses or didn’t find enough egg masses that hit threshold levels. Unfortunately, these farmers were in for a terrible shock when they found heavy damage to their crops at harvest. In some of the worst-hit areas, farmers saw cutworm injury to as many as one in four cobs.

This strange cutworm disappearing and reappearing act had many farmers at winter meetings asking, “did I get something wrong last season and when should I be scouting and spraying for Western bean cutworm?”

To answer those questions — and find out how farmers can be better prepared to tackle cutworms — I spoke with Jocelyn Smith, a research associate in field crop pest management at the University of Guelph Ridgetown Campus.

DAMAGE FACTORS

According to Smith, several different factors played a part in last year’s high cutworm feeding damage. One major contributor was a cool, dry spring with late rains that created wide variability in crop emergence and maturity.

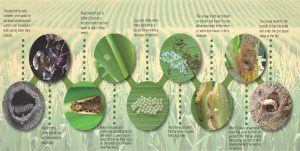

WBC moths looking to lay their eggs during the last half of July are most attracted to corn just before tasseling. This is considered to be ‘peak moth flight’ time and growers are encouraged to scout for egg masses during this time.

Given the variability in crop maturities, growers may have gone in at the correct scouting time during the 2016 season, but did not see egg masses because the corn in their field wasn’t yet at the right pre-tassel stage.

“It was almost as if — due to the wide range in crop emergence — the usual egg laying period was staggered, or broken up over a longer period of time,” explains Smith. “In some areas, for example, we had pre-tassel corn for nearly two weeks, which extended the time that moths were attracted to those fields to lay their eggs.”

Smith also points out that cutworms may have overwintered further north than usual, appearing in areas that were previously not known to be hotspots for the pest.

“Typically, we’ve seen the majority of Western bean cutworm flights originate in regions with sandy soils and then radiate outward, with moths laying eggs for a two to three week period,” she says.

SCOUTING AND CONTROL

Because of the unusual, elongated egg laying period this past season, Smith recommends growers start scouting for egg masses in the second or third week of July and continue scouting every five to seven days until they reach threshold. Growers should add up the amount of egg masses they see each time they scout to determine the cumulative number of egg masses towards the five per cent spray threshold.

“You really need to be vigilant and walk those fields every week, as you might see one percent at first and then in five or six days, the number of egg masses could jump to as high as three or four per cent,” explains Smith.

Smith says the spray threshold for egg masses was lowered from eight percent (eight egg masses per 100 plants inspected) to five percent (five egg masses per 100 plants) for the Great Lakes region. However, considering the mycotoxin problems frequently encountered in Ontario, researchers are considering lowering the threshold even further.

While it’s now too late to consider planting options for this year, it is important to recognize that trait technology has a significant role to play in managing and effectively controlling WBC. Planting seed with this technology is the first and most proactive approach to control. My company (Syngenta), for example, offers the Agrisure Viptera trait technology, which controls a broad spectrum of lepidopteran corn pests including WBC, protecting against yield and quality losses from these insect pests.

With this in mind, let me close with three simple steps to follow moving forward to support your WBC management efforts.

1. Look for corn genetics with effective trait technology to control this pest

2. Practice good scouting for egg masses starting in mid-July

3. Be ready with timely foliar sprays if scouting determines you have met the spray threshold

Shawn Brenneman is an agronomic sales representative with Syngenta Canada covering Middlesex, Elgin, and Lambton. •