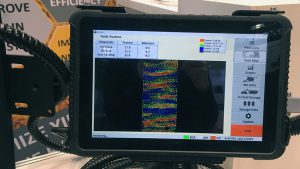

Spore trapping-analysis technology

MANAGING FUNGAL DISEASES

MANAGEMENT OF FUNGAL crop pathogens continues to evolve as new diagnostic tools become available to help farmers understand what diseases are present in their fields and pinpoint whether and/or when to spray.

Systems that trap fungal spores in the air and identify both the pathogens and their ‘threat level’ have been around in Canada since at least 2002. That year, scientists at Phytodata (a company formed by the Quebec horticulture growers’ association Prisme) commercialized a spore-trap system for onions, in collaboration with scientists at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. A group in England called Burkard had already been using rapid DNA analysis to determine spore species for fungal diseases in field crops.

Here in Ontario in 2018, a system called Spornado Sampler was invented and commercialized by scientists Kristine White (CEO), Mike Saleh (chief technology officer) and Dr. James Scott. Since then, in field crops, it has so far been used in Alberta on wheat and barley (Fusarium head blight) and canola (Sclerotinia/white mould).

HOW IT WORKS

The Spornado traps spores in a proprietary membrane in a ‘sample cassette’ that is placed in one or more Spornado trap units set up in a field. At the appropriate time, the farmer or agronomist inserts and removes the cassette and sends it by courier in the provided packaging to Spornado’s partner lab in Ontario, or in Alberta to 20/20 Seed Labs.

At the lab, DNA analysis is used to identify the types and amounts of trapped spores, and for some diseases, an algorithm correlates the results with the number of spores present in the air where the sample was taken. Results are texted or emailed to farmers within 24 hours. For horticultural crop diseases, farmers are given ‘positive’ or ‘negative’ results for diseases, and for field crops, farmers are informed of which diseases are present and a risk level (low, medium, or high). Farmers use this, in conjunction with their own crop scouting, to decide if, or when, to spray.

USER PERSPECTIVES

Paul Kanning farms in Montana about 18 kilometres south of the Canadian border and used Spornado this year. He had heard about it through ads for Manitoba Ag Days (he was going to attend but it was cancelled due to COVID-19) and an article online. He used two cassettes to test for Sclerotinia in his canola about five days apart in July, and says it was very useful and reassuring to know no Sclerotinia was detected.

“Next year, I’m going to get another unit to cover more of my farm,” he says. “I also shared the results with my agronomy co-op and they were very interested.”

Darwin Kells, an agronomist at Lambton Agra Strategies and a farmer in Elfros Saskatchewan, started using Spornado tests last year and has four units on his farm, for canola and barley (neither Kells nor his current clients happen to grow wheat right now). “The system is a convenient way to get an indication of spore level, which can be correlated with overall infestation level,” he explains.

Last year and this year, Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture extension staff have been working with Kells to monitor levels of Fusarium in sprayed fields of barley with untreated test strips. (Note that for malting, barley cannot have any Fusarium, so all fields are sprayed every year.)

Kells placed some Spornado units nearby the test strips in order to better understand what a test result means — that is, if you get a ‘medium’ result before you spray, what level of infestation is present in the untreated test strips later in the season, and what is the eventual effect on yield?

Kells adds that Spornado results are also useful to see how much spore concentration increases over time in order to properly time spraying. He had cassettes analyzed once a week in July during both years, but says ideally tests should be done every three days.

Overall, Kells says the Spornado system “is much more convenient than petal testing in canola for Sclerotinia, the turnaround time is fantastic and the cost is reasonable. It will become more useful over time as the test results become more meaningful.”

THOUGHTS FOR ONTARIO

The success with western crops may not translate to Ontario given our different history and current prevalence of certain pathogens.

Albert Tenuta, field crop plant pathologist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, notes that detecting fungal spores present does not mean you will have disease in the crop — the environmental conditions must be favourable. He says spore analysis technology can be helpful for farmers to focus their scouting, and to tie in test results with other forecasting tools such as ‘DONcast’ for wheat or some others that are being developed.

With Fusarium head blight in Ontario, especially in wheat but also in corn, Dr. Art Schaafsma, professor of Field Crop Pest Management at the University of Guelph Ridgetown Campus, notes that spore concentration is not what determines an epidemic. That is, FHB spores are prolific and very mobile. Therefore, what is most important to consider in spray decision-making is the weather around flowering time: the amount of moisture from rain, dew, and fog, and the temperature (28° C optimum for FHB, range 15° C to 30° C).

Schaafsma believes that for FHB spores in Ontario, “there is no sense in spending any resources keeping track” of them. “I would see Manitoba, especially the Red River Valley, as being more similar to Ontario with lots of spores flying around,” he says, adding that “I can perhaps see [the use of spore trapping technology] in Alberta where FHB is only a recent development.”

White says that there are already about 150 Spornado samplers deployed in horticulture in Ontario, and that her firm continues to add to the 12 fungal diseases already tested for, in horticulture and field crops.

“The genes of most fungal pathogens have been identified and adding a new pathogen to our roster does not take long,” she explains. “In field crops, we are looking next at applying our white mould test to soybean, to ear rot of corn, and stripe rusts (Puccinia striiformi) in wheat, which is increasing in significance all over the continent. Also, tar spot of corn, which is increasing in prevalence in the U.S. and emerging in Canada.”

All of these tests are expected to be available in Ontario in 2021. •