Climate change is changing weeds

RISING CO2 LEVELS MAKE MANY WEEDS MORE COMPETITIVE

ATMOSPHERIC CARBON DIOXIDE stood at 325 ppm in 1970. In 2015, that number stood at 400 ppm. To humans this is a small, unnoticeable increase – but plants are paying attention.

Weeds specifically are finding ways to make this change work for them. As the climate changes, that is, weeds are expanding their range and improving survivability in a multitude of ways. This, says Dave Bilyea, weed science technician at the University of Guelph Ridgetown Campus, will have significant impacts on Ontario’s agricultural landscape.

Needless to say, farmers should find this concerning.

“A lot of the time we don’t even realize all the changes that are happening right in front of us with weeds,” says Bilyea. “These have been going on for over 100 years and will continue to change. The air you breathed as a child is not the same as the air you breath now because the concentration [of CO2] has increased.”

STAGES OF WEED INFESTATION

During a Diagnostic Days session in Ridegtown in July, Bilyea explained the general stages of weed infestation as migration, acclimation, and adaptation.

After encountering new conditions or a new area, Bilyea says weeds can experience a “trait shift,” where a regular biophysical process alters in some way to make the plant more competitive (e.g. giant ragweed emerges earlier in the growing season than it did decades ago). This also relates to “plasticity,” which allows weeds to adapt to their conditions in season — a good example being crabgrass, which grows vertically in corn fields but prostrate in lawns. This, says Bilyea, is an ability crops simply don’t possess.

A weed can then find a niche environment in which to proliferate. Foxtail barley, for example, is relatively tolerant to drought and high-salinity environments; this allows it to prosper in narrow bands along highly managed roads like Highway 401. From this bastion, the weed continues to take advantage of opportunities elsewhere.

“Weeds change their dominance in an area by moving as a group,” says Bilyea. “They are always looking for an opportunity to move into a field.”

CLIMATE CHANGE SPEEDING RANGE EXPANSION

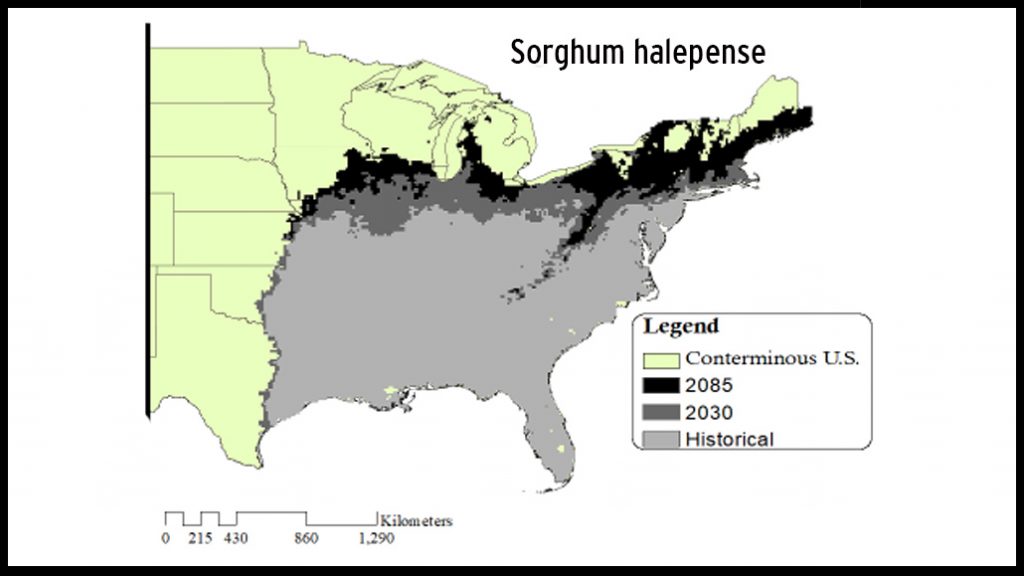

So how does climate change alter weed pressures in Ontario? Bilyea says warming temperatures have helped many weeds to continually increase their range. This applies to both C4 plants — those preferring warmer and drier climes, such as pigweed or Johnson grass — and C3 plants – which prefer more temperate conditions; the latter category comprises approximately 95 per cent of all plants on earth, and the former just one per cent.

Some examples were provided:

• Johnson grass — Once imported as a forage crop in the 1960s, this tall C4 plant was controlled and eliminated from Ontario thanks in part to cold weather. Now it has developed cold tolerant rhizomes, and as Bilyea describes, “is marching to the Canadian border” as average temperatures rise.

• Kudzu — This perennial vine originally from Eurasia can grow 15 to 20 metres every year, and in multiple directions. It’s widespread in the Southern United States, but has developed cold tolerance and now exists in Leamington.

• Green foxtail — A wild grass which has developed cold-tolerance enough to survive as far north as Churchill, Manitoba.

“Growing degree days have changed in a relatively short period of time […] With climate change these things are happening,” says Bilyea.

MORE POTENT PLANTS

Higher levels of carbon dioxide also mean weeds grow larger and more virulently, thus becoming harder to kill. Bilyea provided examples to illustrate additional complications associated with greater CO2 availability:

• Ragweed — A prolific and long-present weed, it now produces greater volumes of pollen (making it more potent).

• Poison ivy — This problem plant now grows larger and produces more potent oil. As Bilyea describes, “the poison ivy of 1960 wasn’t as potent as the poison ivy of today.”

The migration of plant-vectored diseases and insects is also a concern. The aforementioned kudzu vine, for example, is an alternative host for soybean rust and kudzu bug (a notable legume pest). As it spreads, so will the pests and pathogens.

MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES

Not all frontline reports are bad, however. According to Bilyea, climate change might make some problem weeds disappear (or lessen their impact). And just like weeds, higher concentrations of carbon dioxide could also promote crop growth. Winter annuals might also benefit from warmer overall temperatures.

While control measures such as herbicide efficacy will have to change, he adds problems can be anticipated with continuous monitoring. This includes scouting field perimeters where new weeds have a better chance to proliferate. Current problem weeds such as Canada fleabane, he says, show that control is possible with a better understanding of the plant.

“The key thing is we have been able to control a lot of situations,” says Bilyea. “We should always be vigilant because there are always going to be opportunistic weeds that have not been a problem up to this point. Crop scouting is as important as it ever was […] Look for things that shouldn’t typically be there.” •