An all-seeing agronomic tool?

THE CHANGING CAPABILITIES OF SATELLITES

BETTER RESOLUTION, MORE frequent fly-overs, and more refined data interpretation has made satellite technology more useful for farmers looking to improve their agronomic practices.

Limitations still exist, however, though efforts to continually refine the use of satellites for the benefit of both farmers and service-providers are ongoing.

MORE FREQUENT IMAGES

Jamie Denbow, director of business development for Farmers Edge — a farm-data tech company — says the frequency that farmers can access new imagery is a major advantage provided by satellites. His company, based in Manitoba and Iowa, is one of many now offering farmers satellite imagery services, as well as data interpretation services for more immediate on-farm decision making.

Four years ago, says Denbow, farmers could only access new field images every 12 to 14 days. This has changed drastically with an increasing number of satellites now circling in Earth’s orbit.

“Now we’re providing a usable image every day or two days. Growers can use the imagery to make a decision,” he says.

MORE DISCERNING EYES

The resolution and scale of satellite imagery has also improved considerably. Indeed, Denbow says the deliverable scale was, as of four years ago, limited to an average of 10 metres. Now, about 85 per cent of his company’s services operate at the three-metre level.

Combined with more frequent image delivery, he says, this gives farmers the capability to quickly identify problems in the field without having to walk each one, and pointing out specific areas where physical investigation might be required (for example, where a fungal issue has developed, or where one might develop).

This is particularly important for those farming large and distanced tracts of land, since the significant distances between fields makes checking each one impractical.

Tony Balkwill, an agronomist and ag-researcher, also says the most significant driver in satellite technology has been improvements in economy of scale. In his experience evaluating satellite imagery on his research farm in southwestern Ontario, the ability to receive information multiple times a week makes a huge difference in effectiveness.

“It gives us a little direction to scout and ground truth the issue,” he says, adding the increasing investments in image quality made by companies like Farmers Edge are beginning to compete directly with drones.

“The industry is at that point where the tech is good enough and service providers are trying to find a way to profit from it. Growers respect that, but also want to profit from that purchase,” Balkwill says.

DATA INTERPRETATION CRITICAL

Given the sheer volume of data satellite images can provide, Denbow emphasizes the importance of data interpretation. In the case of Farmers Edge, he says an “automated analysis engine” was developed to highlight outliers and differences in field images.

“It’s saying this is a picture of your field, this is an area with a problem we have identified, and we can go [address] that problem directly,” says Denbow, reiterating aggregated data can also be used to develop variable rate application maps for fertilizer, fungicides, desiccants, and so on — supporting more environmentally and economically efficient management strategies.

He adds machine learning is the next frontier in satellite imaging. This will continue to increase precision and identification capabilities.

The cost of satellite tech rises with the level of interpretation. Denbow says imagery alone is at $1.50 per acre for Farmers Edge buyers. Services including imagery, crop models, variable-rate maps, and other applications can be as high as $6 per acre, with price-to-service ratios ranging between.

LIMITATIONS

For Balkwill, the actual effectiveness of the information provided to farmers by service providers is not inherently guaranteed. If some maps are generated using colour-based imaging, for example, and one corn hybrid naturally looks somewhat different from another, it could be misinterpreted as a nutrient deficiency when, in reality, it isn’t.

“They’re still trying to fine tune the end product they are selling farmers,” he says. “A farmer doesn’t need the image, they need a management decision. You just can’t dump 50 pages of images in front of a farmer and expect them to go to work.”

For his part, Denbow says confusion over things such as colour variation is mostly a non-issue. Some “variance layers,” he says, can use colour to identify issues and where different hybrids might be planted. However, he says NDVI imaging (which captures both infrared and visible red light) “is not affected by variety variation and things like that.”

Cloud cover can be also be an issue, as it complicates the clarity of images and their timely delivery. Balkwill says this may not be a notable issue for farmers in the prairies, but it can be for those working in more moisture-prone climates (the entire country of Ireland, for example) or more overcast parts of the year. In such cases, larger-scale drone systems would have to be employed, though camera improvements have somewhat lessened the barrier posed by atmospheric moisture.

Mike Wilson, program lead with Veritas Farm Management — a data service company active in drone use and research — says the metre-level imaging and scalability of satellites have made the technology much more effective and complimentary to drones (which he says can still do some things satellites can’t, such as take pictures at a millimeter scale in cloudy weather).

“They are on different platforms,” he says. “Satellites are just as important. They are probably the more scalable.”

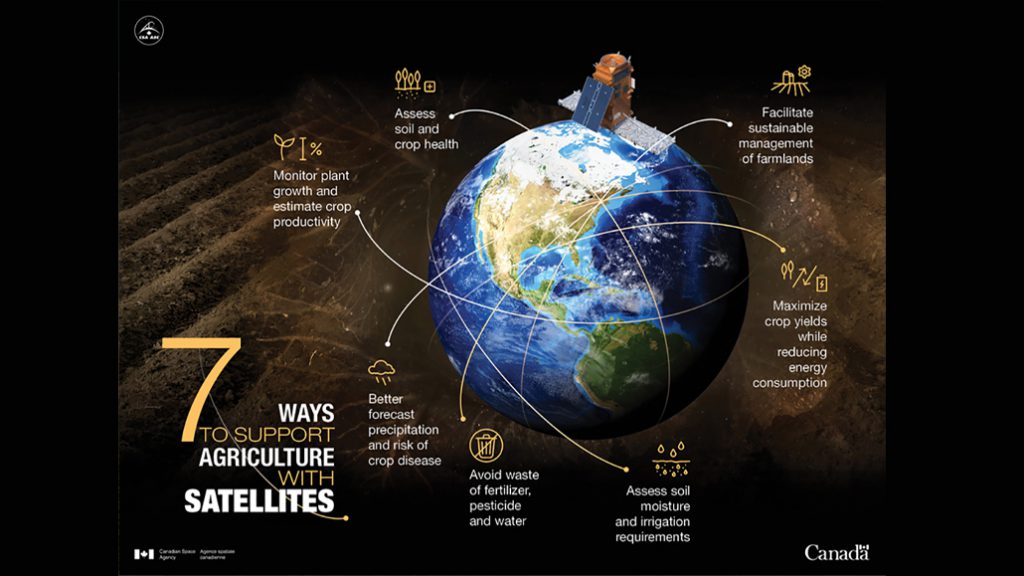

WHAT SATELLITES PROVIDE DATA TO FARMERS?According to the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), farmers can access agricultural data from three main satellites:

Further information about Canada’s agriculture-related space programs is available through the CSA website. |

HAVE A GOAL

Overall, Balkwill says satellite technology can be a valuable tool, and one worth the investment. To make it work, though, farmers should ally themselves with a person or company that can interpret the images into an actual management decision. That means starting with trusted advisors and retailers with experience in map analysis.

Having specific goals in mind — and evaluating the service though in-field comparison trials, or by some other means — is also critical.

“They need to have a bullet list of what you want from the imagery, and push that with the provider — or else you’ll just get a bunch of pretty maps,” Balkwill says. •