Crop diseases

WHAT TO WATCH FOR IN 2020

IT’S HARD TO know exactly what to expect in terms of disease from year to year, since so much is weather dependent, but Albert Tenuta, plant pathologist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA), reminds farmers to keep diseases on their radar.

While new diseases get a lot of hype, Tenuta cannot reiterate enough the importance of keeping a close watch on endemic diseases that are already present.

“Don’t forget about them,” he says. “They can cause you problems every year, depending on the environment, field history, and the hybrid/variety.”

WHEAT

Although it’s still the primary concern when it comes to disease in wheat, there is good news on the Fusarium head blight front, says Tenuta. We’ve seen advancements in both genetics and in terms of fusarium management options, such as new fungicides. Farmers have also done a very good job in terms of the timing of fusarium fungicides for disease control.

“And so we’ve seen, even in environments with favourable conditions for Fusarium head blight, not the same level of infection over the past three to four years than what we would have seen maybe 10 or 15 years ago,” says Tenuta. “We have definitely made significant advances.”

“We are not done, though,” he adds. “There still needs to be more work done on varieties as well as agronomic practices to minimize or reduce producers’ risks to Fusarium head blight, as well as the mycotoxin DON risk.”

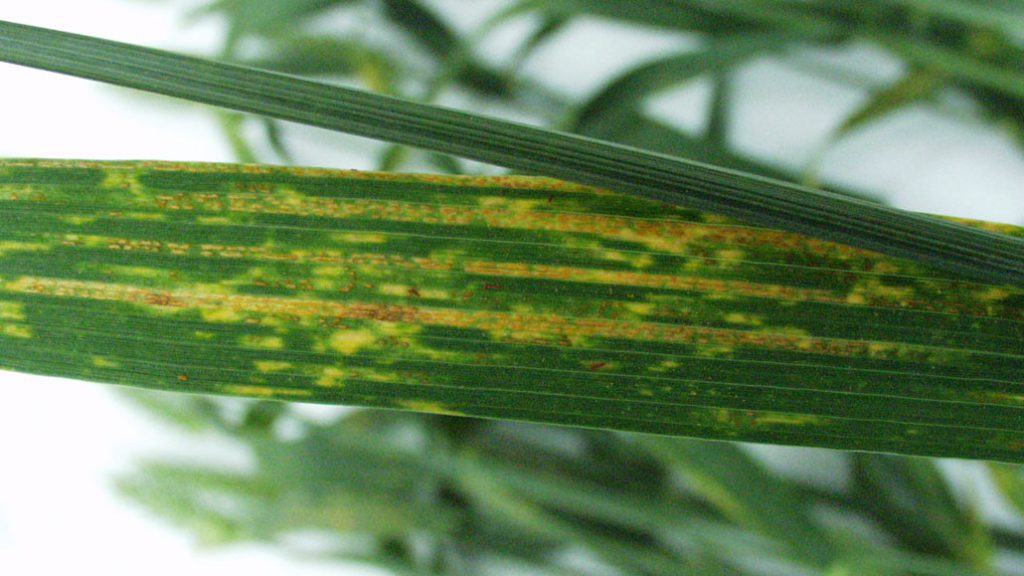

A disease of interest that has popped up on the radar over the past few years is stripe rust. In 2016, for example, there were significant issues with stripe rust in Ontario, particularly in southwestern Ontario. Tenuta says it was the result of warmer than normal winters.

Late fall and early spring infection in the mid to southern U.S. led to the most stripe rust inoculant seen to date. That inoculant resulted in early season stripe rust infections that in some cases occurred prior to flowering and heading.

“With stripe rust, the development of disease can be rather rapid,” Tenuta says. “Two weeks can lead to significant issues and damage potential yield.”

Better awareness and management of stripe rust in the U.S. Midwest, as well as improved genetics and fungicides, should help lower inoculum loads, though.

“Rusts are obligate parasites. They do not survive on non-living plants, so they do not typically survive in Ontario,” says Tenuta. “That’s why that inoculum load is so important, and how early it comes up from the U.S. is critical to whether or not we have issues around those rust diseases for wheat and corn.”

NEW CORN DISEASES

With regards to corn disease, the spotlight is on tar spot. While tar spot is not in Ontario or even Canada yet, it is right on the border. The disease is relatively new, having first been discovered in the 2014–2015 growing season in Indiana and Illinois. Farmers there started noticing lesions on the leaves of their corn crops. Prior to that, it had been confined to specific regions in Mexico. It is thought that disease spores were dispersed by air.

Tar spot remained in the region from 2016–2017, and then expanded a bit. But it was more cosmetic, providing more of a learning opportunity rather than being a cause for panic. In 2018, however, the conditions were perfect for tar spot throughout much of the Midwest from Iowa right through to Michigan. It caused significant yield losses, in some cases 30–40 bu/ac were lost.

By 2019, most of southern Michigan, right up to the Ontario border and down to the Toledo, Ohio area, was infected.

“We do an annual Ontario disease survey with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Ottawa for corn, funded by Grain Farmers of Ontario and the Canadian Agricultural Partnership (CAP) program,” says Tenuta. “And we did not see it again this year, which is good, but I do expect that we will see it sometime over the next year or two.”

The good news is that because these diseases impact growers both north and south of the border, finding a solution has become a team effort. Groups such as the Crop Protection Network bring together extension specialists and researchers from Ontario and the U.S., all with the common goal of finding a solution to combat these crop diseases and to inform growers of their most recent findings.

The Crop Protection Network, also supported through Grain Farmers of Ontario funding, offers information on the biology and management of tar spot and many other diseases.

“Tar spot is near. It’s one disease we’re highly aware of, and we are actively putting things in place to prepare for its eventual arrival in Ontario,” says Tenuta.

In terms of what farmers need to watch for in 2020, Northern corn leaf blight continues to be the number-one foliar disease of concern. It continues to show up in surveys. Almost every field has Northern corn leaf blight, so incidence is high. Severity varies from location to location due to differences in hybrids, environmental variability, and differences in management.

Tenuta urges farmers to review selected hybrids/varieties for their disease profiles to prepare themselves for those diseases that they may be more susceptible to. Look for hybrids/varieties with good resistance if it has been a problem in your area.

Another important corn disease to watch for is Gibberella ear rot. Caused by the fungus Gibberella zeae, it is a mycotoxigenic fungus in major corn-growing regions that produces vomitoxin, zearalenone, and other toxins.

In 2018, conditions created the perfect storm for Gibberella ear rot. The outbreak, though, led to greater awareness in terms of hybrid selection and breeding efforts. New fungicide options are also performing well, and fungicide timing is better understood, says Tenuta.

Finally, Grain Farmers of Ontario along with OMAFRA, University of Guelph Ridgetown Campus, the Ontario Agri-Business Association, and key stakeholders have formed a mycotoxin working group with the aim to reduce variability in testing at elevators.

SOYBEAN CYST NEMATODE

Soybean cyst nematode (SCN) is a good example of an endemic disease that growers sometimes forget about when it doesn’t rear its head for several years. But it should remain high on farmers’ radars, says Tenuta.

“If you don’t see it, you tend to forget about it,” he says. “But that doesn’t mean the nematode has forgotten about you. The nematode hasn’t forgotten about what it wants to do and that is to reproduce.”

In recent years, Tenuta says they’ve seen an increase in the amount of SCN in fields throughout the province, but particularly in southwestern Ontario.

The other big change that has occurred with SCN is that the ability of field populations to reproduce on resistant varieties has increased.

“It has become a better pathogen,” says Tenuta. “So SCN has started to increase more on what traditionally had been very resistant varieties containing the PI88788 source in Ontario.”

Rotation with other sources of resistance, such as Peking, is always a good idea, says Tenuta. There are not a lot of varieties available for the Ontario market, but more are being introduced every year so check with your seed dealer or consultant.

Farmers should sample their soil to evaluate risk and to evaluate how management has impacted SCN populations. One good management tool is lengthening rotations.

“Growers need to be aware of the risks of growing too many soybeans in the rotation,” cautions Tenuta.

More information on management can be found on the SCN Coalition website. The SCN Coalition brings together expertise from OMAFRA and the U.S., and Tenuta’s participation is supported by Grain Farmers of Ontario through CAP funding.

The good news on the SCN front is the introduction of seed treatment nematicides.

“None of them are silver bullets, and it’s important for producers to understand that seed treatment nematicides, if used, will not eliminate soybean cyst nematode,” says Tenuta. “It will not kill them all and you will still have soybean cyst nematode at the end of the year. Field evaluations continue especially as new products come to market”.

All other tools, including variety selection, soil sampling, and crop rotation, must still be included in a SCN management plan.

Another disease to watch for in soybeans is Sudden death syndrome (SDS), which has become more established across the province. A strong management strategy, says Tenuta, includes variety selection, SDS-specific seed treatments, and lengthening rotations.

DON’T FORGET ENDEMIC DISEASES

While diseases such as soybean cyst nematode, tar spot, and Northern corn leaf blight tend to take up the spotlight, Tenuta reminds farmers not to forget other important diseases such as white mould and phytophthora root rot in 2020. Farmers should be scouting their crops throughout the growing season. •