Getting the dirt on corn nematodes

AN UNDERESTIMATED AND MISDIAGNOSED PARASITE

do you have fields or pockets of land that seem to have chronic yield and health problems no matter what strategy you use for crop rotation, weeds, pest management or fertility? Corn nematodes could be holding you back.

That’s the word from two field crop plant pathologists and extension specialists. They say the effect of parasitic corn nematodes is being underestimated and misdiagnosed in grower’s fields. Dr. Tamra Jackson of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and Albert Tenuta of the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture Food and Rural Affairs are researching and building awareness of the issue.

“Corn nematodes have been a historical problem in our growing region, we just haven’t addressed or talked about it again until recently,” says Jackson, adding that because nematode symptoms mimic those of other crop issues that are commonly seen, corn nematodes are not often considered or known as possible causes to explore.

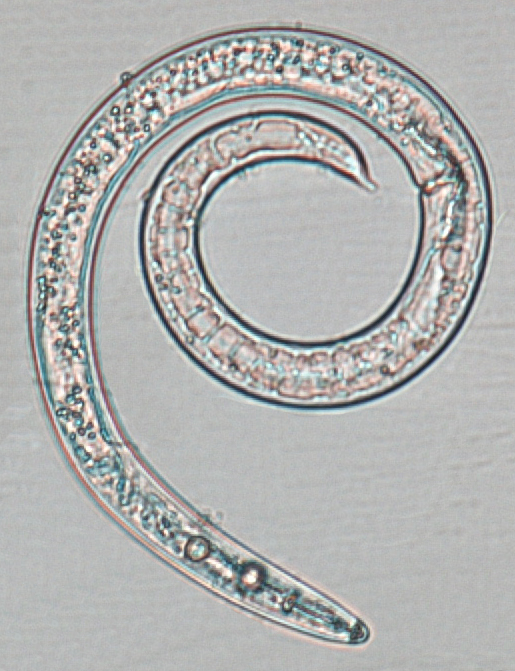

PHOTO 1: SPIRAL NEMATODE

Digging into the topic reveals that there is minimal information about these complex microscopic parasites that are being found to wreak havoc on crop yields and plant health. “Corn nematode knowledge today is where we were 20 to 25 years ago with soybeans,” Tenuta says, referring to the gap in nematode information. He says it took the discovery of soybean cyst nematode in Ontario in the 1980s to fuel interest in its control so growers could minimize losses. Now the spotlight is turning to corn.

so what information is known about corn nematodes?

Common symptoms that might be associated with nematode damage include poor or uneven stands resulting in reduced yields, yellowing of foliage, and small or poorly filled ears. Damaged roots can have lesions, be stunted, discoloured, swollen, or lack fine roots. Certain types of nematodes such as needle and sting can create severe damage in localized areas, whereas other more common nematodes display more subtle symptoms that can extend over larger areas.

Unlike soybeans, which are mainly dominated by soybean cyst and root-lesion nematodes, corn issues can be caused by a wide range of nematodes, say Tenuta and Jackson. Some nematodes can affect entire fields, while others are more localised and create ‘hot spots’. Some prefer sandy soil, while others can survive in any soil type and some are crop specific, while others can cross-over to soybeans, wheat and other field crops.

Most plant-parasitic nematodes have a hollow, pointed, sharp stylet that allows them to puncture root cells and feed on the contents. Jackson says corn nematodes can be described by the manner in which they feed on the plant. Ectoparasites, such as needle and sting nematodes, feed from the outside of the root while endoparasites, such as root-lesion nematodes can feed on both the inside and outside of the roots. These endoparasites have often been ignored and their damage underestimated. Root-lesion nematodes are present in more than 80 per cent of midwestern US corn fields and are believed by most nematologists to cumulatively cause the most damage to corn, Jackson says.

Additionally, the wounds created by nematodes could provide an entry point for root rot pathogens such as Fusarium, Rhizoctonia, Pythium and others.

The only way to confirm and diagnose the presence of microscopic corn nematodes is to collect samples, says Jackson. She emphasizes the importance of submitting both soil and root samples to a lab, such as the Pest Diagnostic Clinic in Guelph, for processing. Because of the endo- and ecto- nature of the parasites and where they feed on the plant roots, relying on only a soil or only a root sample will reveal just part of the picture.

It’s very important to obtain samples from the area of the root zone, Jackson says. Extra care should be taken when sampling sandy soils. Needle and sting nematodes, which tend to reside in sandy soil, can migrate several feet into the soil depth – putting them beyond the reach of most soil sampling probes. To combat this, Jackson suggests sampling sandy soil early in the growing season when plants are at the 4 to 6-leaf stage, which means roots – and the parasitic nematodes feeding on them – are still in the upper 8-10 inches of soil.

“Often growers are concerned and surprised when they get their nematode report back,” says Jackson, explaining that it’s not uncommon for the report to list several different species of nematodes being present in a particular field or hot spot. “The key then, to know whether you really have a nematode problem, is to evaluate which types and how many you have.”

STING NEMATODE INJURY HAS DAMAGED AND SHEARED THESE CORN ROOTS

In a recent survey of growers’ fields from Windsor to Toronto, Tenuta says more than 25 per cent of fields were identified as being at or above set values for particular nematode types in their region. “These values were certainly higher than we expected, but not unlike what’s being found in the north-central US,” says Tenuta.

Tenuta believes there are a number of different reasons why nematodes are better able to build-up in the soil compared with a decade ago. He points to changes in the classes of insecticides and mode of action that growers now use as one contributing factor. “We’ve moved away from soil applied insecticides that we now see not only controlled insects but also had influence or suppressed nematode populations,” he says. “We’re also using fewer insecticides and relying more on the abilities of transgenic corn.” In the US, Jackson says high corn prices have also changed the crop rotation behaviour of growers as more are abandoning their rotations in favour of continuous corn.

The biggest challenges facing the industry related to corn nematodes are identifying appropriate thresholds or ranges for the various nematode species, and understanding control measures.

“What’s frustrating is that thresholds for different nematode species are difficult to pin down because they are dependent on so many factors, including growing conditions, soil type and rotations,” says Jackson. “Thresholds for a species might be different for every field, every year, and so the numbers should be used only as guidelines.”

Unfortunately research on corn nematodes is an area that has been largely underserviced in the past, both Tenuta and Jackson say. Lack of funding, a limited pool of nematologists, and limited awareness hasn’t helped. This is changing as new nematicides are coming onto the market, prompting more research into threshold and control measures.

For current growers that have nematode problems, Jackson recommends a multipronged approach. For her US growers, she often recommends strategic crop rotations paired with nematicides as part of control measures. Efforts that focus on overall plant health, including fertility, pest and weed management also seem to reduce plant stress and in turn help prevent corn nematodes from gaining a foothold.

Both Tenuta and Jackson agree that nematicides hold great potential as a management tool for growers in the future. Nematicide products have been approved for use in the US since 2007. In Canada, the first one is planned to hit the market this year.

In the meantime, Tenuta and Jackson will be busy with research, surveys and extension work related to corn nematodes. Presentations on the topic at grower meetings are also gaining momentum and garnering a lot of grower questions. •