Avoiding mistakes with cover crops

UNDERSTANDING DIFFERENCES LEADS TO MORE EFFECTIVE USE

“Don’t mess up an opportunity to do some soil maintenance […] put a cover crop on. It doesn’t have to be expensive.”

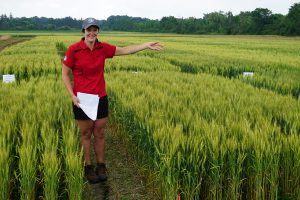

This sentiment was expressed by Anne Verhallen, soil management specialist, horticulture, for the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA). Verhallen, in a joint Diagnostic Days talk with Doug Young, professor at the University of Guelph Ridgetown Campus, encouraged farmers to put some real thought into their soil goals, and how cover crops could help achieve them.

But incorporating cover crops into one’s rotation, they say, requires some strategic thinking. That means accounting for what immediate problems need to be addressed, long-term strategies, as well as the growth characteristics of individual cover crop species – and what they can do.

BASIC CONSIDERATIONS

So, you’ve identified a goal (e.g. compaction reduction, soil structure improvement, etc.) and are looking for the right cover for the job – what are some important initial considerations?

According to Verhallen, applying a cover after wheat tends to be easier since the growing season is at least two months. But specie selection needs to fit your rotation order, what you plan to spray, and what crop will be planted the following season.

If the intention is to plant a given field with soybeans, for example, adding leftover soybeans to a preceding cover crop might not be desirable. Herbicides like Atrazine also have residual effects that need to be accounted for.

“Its terrible to put the money in to a cover crop and have it grow poorly, or not at all, just because you have some herbicide residues,” says Verhallen.

Farmers can also consider whether a single specie will do the trick, or if a mixture might provide better results. As an example, pairing a taproot with a fibrous root system, say both Verhallen and Young, can better support compaction reduction as well as soil structure improvements.

Oats and other cover crops with fibrous roots, that is, are better for the latter, while taproot crops like tillage radish are better at combating the former. That said, fibrous root species do have some anti-compaction abilities as well.

“You need to tailor your mix [to your] needs,” says Verhallen.

Seed size is another consideration since it affects how cover crops can be planted. Small seeded crops like annual rye and red clover, says Young, can be broadcast, and light tillage can be applied for fast growth results. However, he adds broadcast cover crops “need rain to be successful.”

Conversely, large seeds (such as peas) need to be applied with a drill. Regarding mixes, Young says the largest seed will determine how the cover is applied – which, in mixes, tends to mean a drill is required.

Cover crops need the right amount of time to develop, too. That means accounting for the maturation time of each species and your growing reality. Red clover, for example, can take a long time to grow, so applying it at season-end doesn’t allow for sufficient growth. Conversely, oats mature comparatively quickly; this makes the specie less suitable for longer cover crop seasons – or on this year’s increased number of unseeded acres, for example.

Last but not least – the dollars and cents. Some covers are more expensive per pound, others less so. Some require additional inputs (e.g. nitrogen) to reach their full potential, others not so.

“Things can add up quickly in mixes,” says Young.

Just because a cover crop or mixture involves larger short-term costs, though, doesn’t mean it’s not worthwhile. The initial price-tag should be considered and balanced with both long-term and more immediate soil goals.

Regardless, Young reiterates “rotations with cover crops tend to yield more than those without.” With some additional nitrogen for increased biomass, he adds, many cover crops also make good animal feed.

COMMON MISTAKES

For those trying mixes, Verhallen says it’s critical to know both what species are in the mix and the growth pattern of each one. For example, buckwheat can be a good cover crop, but its ability to flower and set seed in six weeks can cause major management problems. This makes ill-suited for mixes with slower-growing counterparts.

Knowing how and when the crop is going to die (having a termination plan) is also important, as is a “Plan B” in case things go awry.

Everything hinges on good research. Verhallen recommends the Midwest Cover Crops Council as an effective information source on both single species and basic mixes.

COMMON COVER CROP OVERVIEW

A number of common cover crops were showcased during Verhallen’s and Young’s diagnostic days presentation:

- Buckwheat – Quick growing and generates significant biomass. Termination should occur before it grows too large.

- Tillage radish – Very strong expanding taproot. Requires 50 pounds of nitrogen per acre to start.

- Peas – A nitrogen-fixing crop, but one without a dense root system.

- Sunflower – Generates plenty of deep roots. It is also a dryland crop that requires both water and some nitrogen.

- Red clover – A common cover crop used in underseeding because of its comparatively slow growth.

- Oats – Fast-growing with deep, fibrous roots, oats do not overwinter and thus are easily managed. Also effective at suppressing fleabane, though less so compared to rye.

- Annual Rye – This “quick perennial” is good for building soil structure. However, it can be tough to kill.

- Cereal Rye – Good for building soil structure but easier to kill than annual rye.

- Winter Rye – A short winter annual with lower root depth and density than oats, but provides good cover when its needed for longer periods of time.

- Winter canola – This crop has an extensive root system and will overwinter.

- Sorghum Sudan grass – A corn-like grass hybrid with large top roots. Can be used for forage.

Further information on these and many other species, as well as management strategies and best uses, can be found on the OMAFRA website: