Water management

IMPROVEMENTS THROUGH SOIL HEALTH

Water is a precious resource. The success of farm businesses and the health of our families depend on having a clean and abundant supply. Historically, agricultural technology has allowed us to manipulate the quantity and quality of water supplies to increase productivity. Today, this continues, with new technologies and a better understanding of natural processes. This article is the third in a series focusing on modern management of water for grain farms. Go to www.ontariograinfarmer.ca for more information and previous articles.

THE PREVIOUS TWO articles of this series, have discussed how important water is to agriculture, the challenges associated with rainfall deficits during the growing season, and the critical role that tile drainage plays in removing excess soil water rapidly. In this article, we will focus on how you can improve water management through good soil management. We will explore how to enhance your soil’s ability to absorb rainfall and provide a greater amount of plant available water.

| SOIL COMPACTION AVOIDANCE AND MITIGATION • Be patient — do not put equipment on wet soil whenever possible • Watch the weight — don’t fill the grain buggy or manure tanker under less than ideal conditions • Use the biggest, highest tech tires you can afford (consider the savings in soil damage versus the cost of tires) • Optimize tire pressures for the conditions • Adopt automated central tire inflation/ deflation systems to optimize tire pressure for field and road conditions. Compromising on pressure between road and field is a lose-lose situation. |

HOW WATER BEHAVES IN SOIL

A soil’s texture and landscape position strongly influence how water behaves within its profile. Coarse soils in high landscape positions drain excess water rapidly and have a low water table; they don’t do a great job holding available water for crop use. Poorly drained soils, on the other hand, are found in lower landscape positions, have a high water table, and are often comprised of fine-textured soil particles that transmit water very slowly through the profile.

While sub-surface drainage allows us to remove excess water more rapidly, it works much more effectively when soil allows water to move in and through the profile well — this is where good soil management comes in.

Soil management is also key to building soil that holds onto and provides plenty of available water to crops, especially in the heat of summer. To understand why this is, let’s first talk a little bit about a critical component of healthy soil — empty space.

SOIL PORES

As you’ve likely heard before, an ideal soil by volume is made up of about 45 per cent sand, silt, and clay, five per cent organic matter, 25 per cent air and 25 per cent water. That’s right, half of what we typically think of as a solid material — soil — is comprised of empty space, or pores. Why is this so important? To function properly, plant roots and soil organisms need oxygen, water, and space to grow and live. Soil is a vital living ecosystem, after all. Oxygen must be taken in and carbon dioxide exchanged back out into the atmosphere. Too little water means plants and soil life suffer or die, while too much means that air exchange can’t occur, which results in detrimental anaerobic conditions.

Soil pores can be small, medium, or large, and exist between individual soil particles or between clumps of particles, called aggregates.

The largest pores allow for quick drainage because they can’t hold water against the force of gravity. These pores are often found in coarse-textured soils such as sands and loamy sands. Bio pores, formed by the actions of earthworms or old root channels, are often larger and drain freely.

The smallest pores, which exist in great abundance in fine-textured and compacted soils, hold water so tightly that it drains very slowly and can’t be easily accessed by roots. Medium-textured soils, such as loams, have a variety of pore sizes and, when well-managed, have a high proportion of medium-sized pores, which drain moderately and are accessible to plant roots. This is why medium-textured soil is inherently easier to manage and more resilient across a range of moisture conditions.

GETTING WATER INTO THE SOIL

When water falls on a bare field during the growing season, typically around two-thirds is evaporated back to the atmosphere, one quarter runs off, and the remainder infiltrates into the soil and is stored, taken up by crops, drained, or re-charges groundwater. These proportions vary across seasons and soil types.

When it comes to water management, many factors are out of your control as a farmer. Water infiltration, however, is one aspect that you can influence. Although all soils infiltrate water differently based on texture and slope, residue cover, and surface structure greatly affect infiltration rate. Crop or cover crop residue on the soil surface lessens the force of rain, which provides more time for it to soak in and reduces the erosion potential. Well aggregated, crumb-like soil holds its shape and allows water to move into the soil instead of running off. We have seen this time and time again with rainfall simulations that we have run at events (Figure 1).

Once water has entered the soil, how quickly it moves through the profile depends not only on soil texture, but also on the number, size, and continuity of pores. Macropores, such as earthworm burrows, old root channels, and cracks, transmit water rapidly and can greatly enhance infiltration rates, particularly during storm events. While they can be conduits for nutrients, using good nutrient stewardship and soil management practices reduces risk of loss.

Dense layers of soil, whether caused by surface crusting (Figure 2), a tillage pan, or subsurface compaction, can restrict the downward movement of water during a rain event. When water encounters a layer of very small pores, it gets held up and can’t move down the profile as effectively. Fibrous-rooted small grains, perennial forages, and deep-rooted cover crops help re-connect soil layers and improve water movement. If the compaction is severe, ripping just below the compacted layer, followed by the seeding of an appropriate cover crop, may also be warranted. Varying the depth of tillage and adopting compaction avoidance and mitigation strategies can reduce the likelihood of a pan developing.

HOLDING MORE PLANT AVAILABLE WATER

How soil holds water is similar to a sponge. Once a soaking sponge freely drains from its larger pores, the water that is left is held in small and medium-sized pores. The main goal in soil water management is to infiltrate and transmit water efficiently through the soil; the secondary goal, particularly crucial during the growing season, is to hold as much water in a plant-available form as possible.

Good soil aggregation is the first key to improved water holding capacity. Spaces between aggregates allow for water to drain, while pores within aggregates hold onto water. A continuous supply of crop residues and other organic materials, as well as active plant roots and soil life, are necessary to build and maintain a stable crumb structure. This is why we see the best soil structure in fields with a good crop rotation, lots of living roots, and regular addition of manure. Tillage destroys soil aggregates. When used excessively and not counter-balanced by other best practices, it results in dense, poorly structured soil.

Soil organic matter also plays an important role in increasing the soil water bank. Although recent research suggests organic matter may not play as dramatic a role in water holding capacity as once thought, it has plenty of indirect effects, such as potentially reducing evaporation, enhancing water infiltration, and increasing aggregation. A good target for loam soils in Ontario is four per cent or higher.

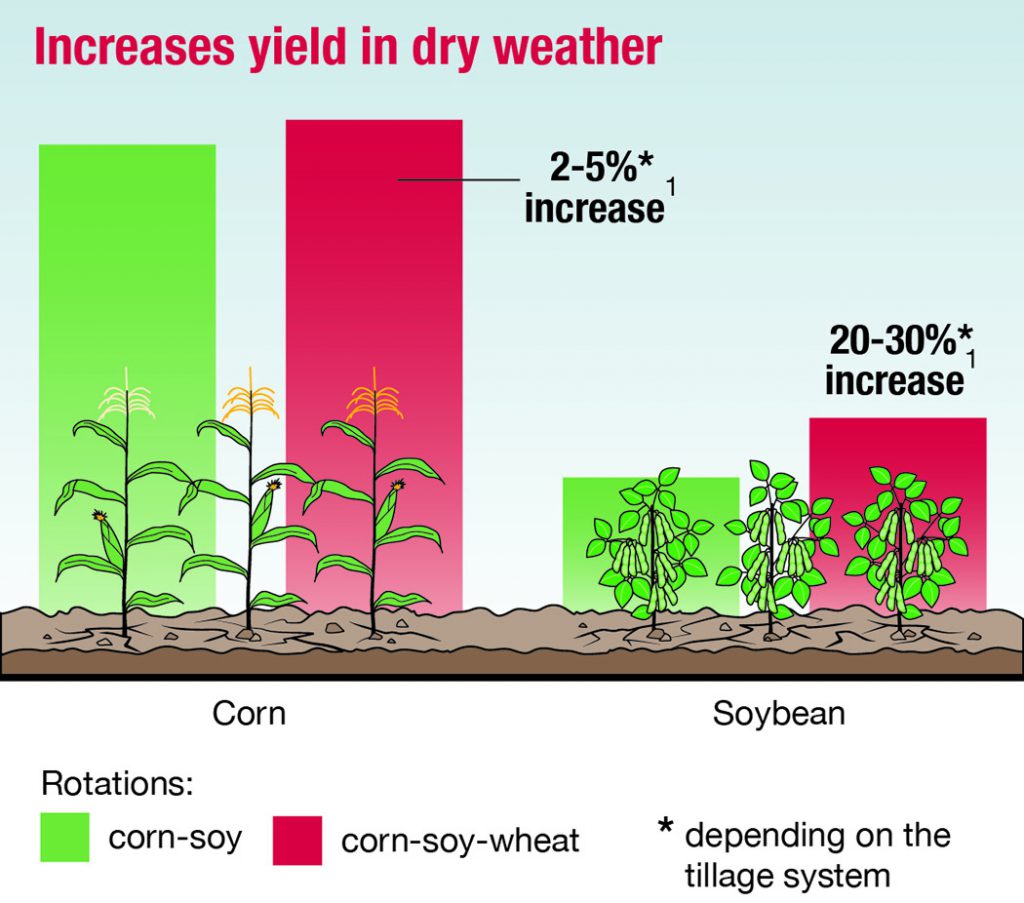

Growing a diverse crop rotation is one of the best ways to increase the soil water bank. University of Guelph long-term research at Elora shows that adding a small grain or forage to a corn-soybean rotation results in two to five per cent and 20 to 30 per cent higher corn and soybean yields, respectively, under dry conditions (Figure 3).

THE BOTTOM LINE

Good water management is one of the most important factors in crop production. Though you can’t control when it rains, how you manage your soil greatly impacts how it handles water, especially in times of excess or drought. It also influences your ability to perform timely field operations and minimize off-farm environmental impacts.

While improvements in soil health don’t always provide immediate results, they show up over time through greater yield stability. As weather from season to season becomes less predictable, investing in improved water management through soil health is a sound agronomic decision. The best time to get started is now.

References: Magdoff, F. and Van Es, H. Building Soils for Better Crops, 2nd Edition. Lincoln, NE:University of Nebraska Press; 1992.

Minasny, B and McBratney, A.B. Limited effect of organic matter on soil available water capacity. European Journal of Soil Science; 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejss.12475. •

Other articles in the series:

• Producing the best grain crop possible (September 2020)

• The water cycle and why should we care (October 2020)

• The role of farm drainage (November 2020)

• Improvements through soil health (December 2020)

• A second look at farm drainage (January 2021)

• Is irrigation of grain crops feasible (February 2021)

• Irrigation case study (March 2021)

• Understanding groundwater (April/May 2021)