Water management

IRRIGATION CASE STUDY

Water is a precious resource. The success of farm businesses and the health of our families depend on having a clean and abundant supply. Historically, agricultural technology has allowed us to manipulate the quantity and quality of water supplies to increase productivity. Today, this continues, with new technologies and a better understanding of natural processes. This article is the sixth in a series focusing on modern management of water for grain farms. Links to more information and previous articles are at the end of this article.

PORTIONS OF ONTARIO grain production areas have suffered from significant droughts in three of the last 10 years (2012, 2016, and 2020). With improved genetics and significant investments in crop inputs, some farmers are looking to irrigation as a way to eliminate drought related losses and optimize crop production. When we consider an average of all the grain production areas across Ontario, irrigation is not economically beneficial. However, some soils, locations, and business constraints may make irrigation attractive to some grain farmers. If you are considering investing in irrigation, this article will walk through the main considerations: water supply, permitting, equipment, operating costs, and labour.

Planning and developing an irrigation water supply involves considering the source, costs, convenience, reliability, environmental impacts, and permitting requirements. Options include wells, lakes, rivers/streams and ponds, including landowner constructed ponds.

The first step is to estimate how much water will be needed and at what flow rate; then match the demands to a water source which can sustainability provide that volume and flow of water.

WATER NEEDS

Current Ontario grain corn production could benefit from three applications of 25mm of irrigation in dry summers (total of 75mm/ three inches). The flow rate needed is commonly calculated by multiplying five U.S. gallons per minute (gpm) for every acre irrigated. So, for a 100 acre parcel, you would require a source that can provide 500 U.S. gpm and a seasonal total of at least eight million U.S. gallons (31 million litres).

Will your water source be available in times of drought and meet your needs without interfering with other water takers or impacting the natural environment? Do you need a reservoir or holding pond in combination with another water source? For more information on developing irrigation reservoirs see the Fact Sheet: www.omafra.gov. on.ca/english/engineer/facts/16-009.htm.

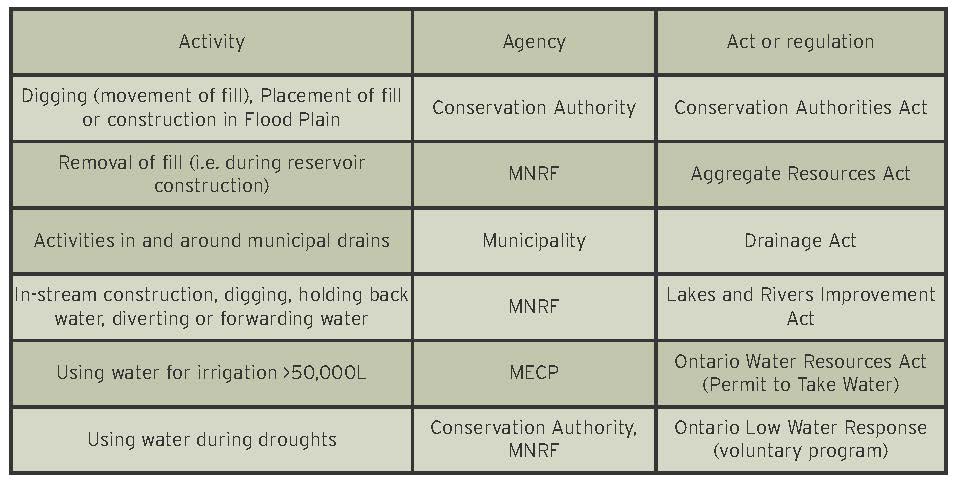

Your water supply must be on the farm or nearby so that the distance and vertical lift between it and your irrigation system are minimized; this will minimize the pumping and infrastructure costs. It is important to consider the environmental implications associated with taking water. Taking large amounts of water from a well may cause reduced water in nearby wetlands, streams, or other farm wells. Taking large amounts of water from a small stream can have a major impact on the stream flow. It is illegal to restrict stream flow either by pumping or by constructing a temporary dam (such as with sandbags) to create a pool for irrigation without the necessary permits. Table 1 shows a list of some of the relevant regulations that apply to water supply development and use.

PERMITS

A Permit to Take Water (PTTW) from the Ontario Ministry of Environment, Conservation and Parks (MECP) is required for any irrigation taking of more than 50,000 L/day (that is ~0.5 acres irrigated with one inch of water).

The PTTW program helps to make sure water is safeguarded and shared fairly among all water users, while maintaining necessary flows to protect the environment. A permit is required even if the taking only occurs one day per year. It applies to all water sources used for irrigation, such as wells, streams, lakes, and ponds, and includes water supplies on the farm property that have been built by the landowner such as ponds collecting surface or tile drainage.

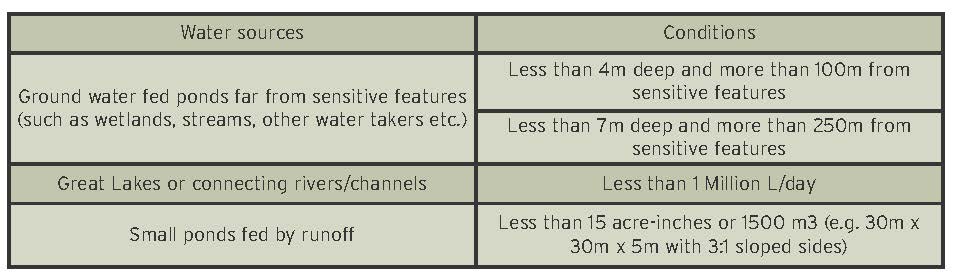

Most PTTW applications will require that you complete a water taking impact assessment (hydrologic or hydrogeological study) by a qualified professional. The cost of this assessment is the irrigator’s responsibility and typically ranges from $10,000 to $50,000.

Table 2 outlines the situations where a hydrologic assessment is not generally required.

PTTW holders must keep records of the daily pumping volumes and report these back to the MECP at the end of each calendar year. PTTW must be renewed before they expire — typically every five or 10 years. Each PTTW is unique and may have other monitoring and reporting requirements. In addition to flow rate limits and daily volume limits, some PTTW have additional limits or cut-offs at certain stream flows or other water level conditions.

For more information, visit Permits to Take Water at www.ontario.ca/page/permits-take-water. There are no fees required by MECP for PTTWs for agricultural irrigation.

EQUIPMENT

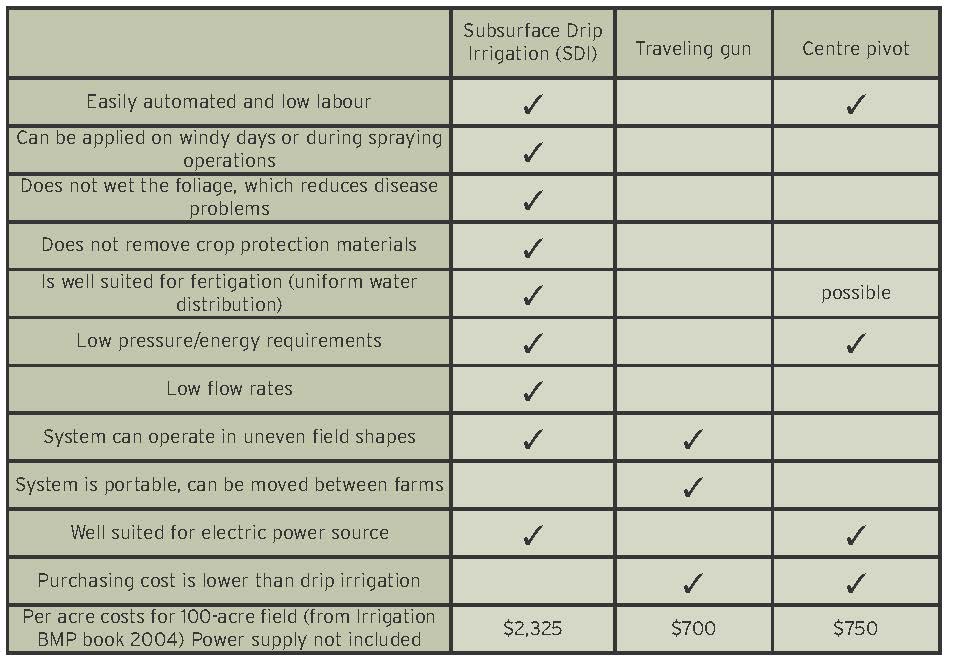

Grain crops in Ontario can be irrigated by drip irrigation (on the surface or buried) or by overhead irrigation (travelling guns or centre pivot).

Drip irrigation is based on the concept of preventing rather than relieving moisture stress. The crop response to this approach is positive. Drip systems are the most water efficient option and are known to generate the most crop per drop of water.

A drip irrigation system supplies a small amount of water to the root zone of the plants. The system components can be downsized because water is delivered more continuously (usually daily, when needed) and only the rooting areas are watered. As compared to an overhead irrigation system, the pumps required for drip irrigation are smaller, less power is required, less energy is used, and the water conveyance lines are smaller.

The buried drip irrigation systems that have been successful in Ontario have drip lines

buried at 14 to 18 inches below surface. Drip line spacings range from 60, 44, and 30-inch spacings with slight yield benefits from narrower spacings. Buried systems must have both a header and footer manifold pipe to maintain water flow throughout the network and for periodic flushing.

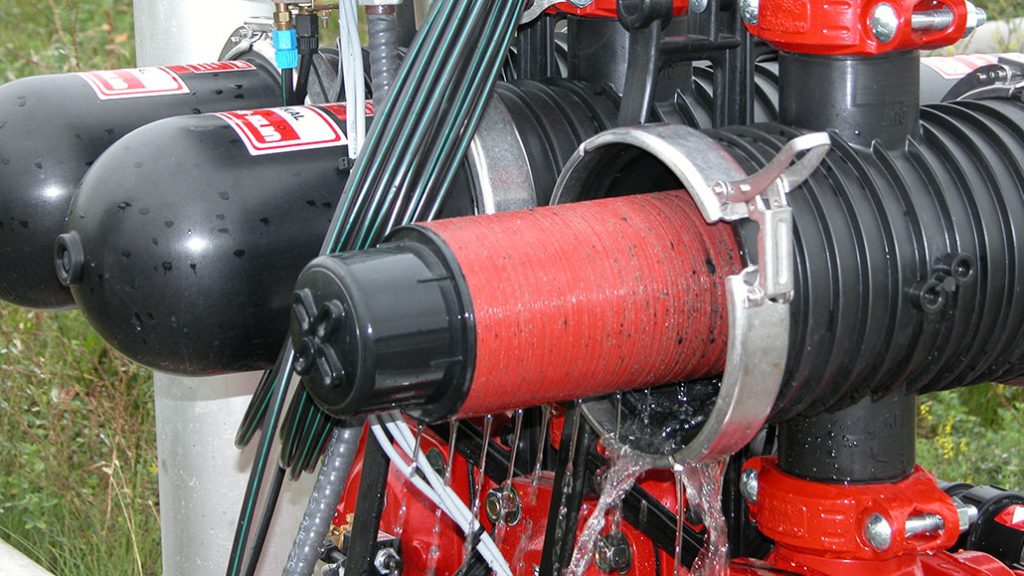

Drip systems require filtration units to provide clean water and avoid emitter plugging (Figure 1).

Overhead irrigation is based on replacing the amount of water used by the crop after a certain time period, usually every five to 10 days.

The overhead irrigation systems that have been successful in Ontario are traveling gun and centre pivot. The traveling gun is the most common irrigation equipment because of its low capital cost and portability to different fields. Traveling guns require significant labour to move and operate; they also have high power/energy requirements. Centre pivots are the equipment of choice for grain farmers in Michigan. They also have low capital costs compared to drip but can be automated and have lower power/energy requirements than traveling guns. Their disadvantage is that they irrigate a circle pattern, so are best suited to a square field.

MANAGEMENT

In addition to the basic labour requirements of setting up and operating an irrigation system, there are also management choices that need to be made. When should irrigation be started? How much should be applied? A flow meter is an essential component of an irrigation system package. No manager can do a good job without knowing how much water is being used, when, and on what fields. Decision making tools such as soil moisture monitoring probes and/or weather stations are also important for success.

Irrigation ensures that the season’s crop inputs are fully optimized for the crop — making efficient use of seeds, fertilizers, crop protectants, fuel, equipment use, and labour. But venturing into irrigation involves a new level of permitting, environmental considerations, and management.

The next and final article in this water series will focus on grain farm water management and interactions with ground water.

For more information on irrigation see OMAFRA’s on-line resources, videos, and fact sheets at www.omafra.gov.on.ca/english/ engineer/irrigation.htm also see the BMP book “Irrigation Management” which can be ordered free from Service Ontario at www.publications.gov.on.ca/browse-catalogues/livestock/best-management-practice-series/best-management-practices-series-irrigation-management-revised-2004.

This article was written with input from Ian McDonald, Trevor Robak, and John Molenhuis from OMAFRA. •

Other articles in the series:

• Producing the best grain crop possible (September 2020)

• The water cycle and why should we care (October 2020)

• The role of farm drainage (November 2020)

• Improvements through soil health (December 2020)

• A second look at farm drainage (January 2021)

• Is irrigation of grain crops feasible (February 2021)

• Irrigation case study (March 2021)

• Understanding groundwater (April/May 2021)