The best and worst of times

BRAZIL’S STRUGGLE WITH PRODUCTION GROWTH

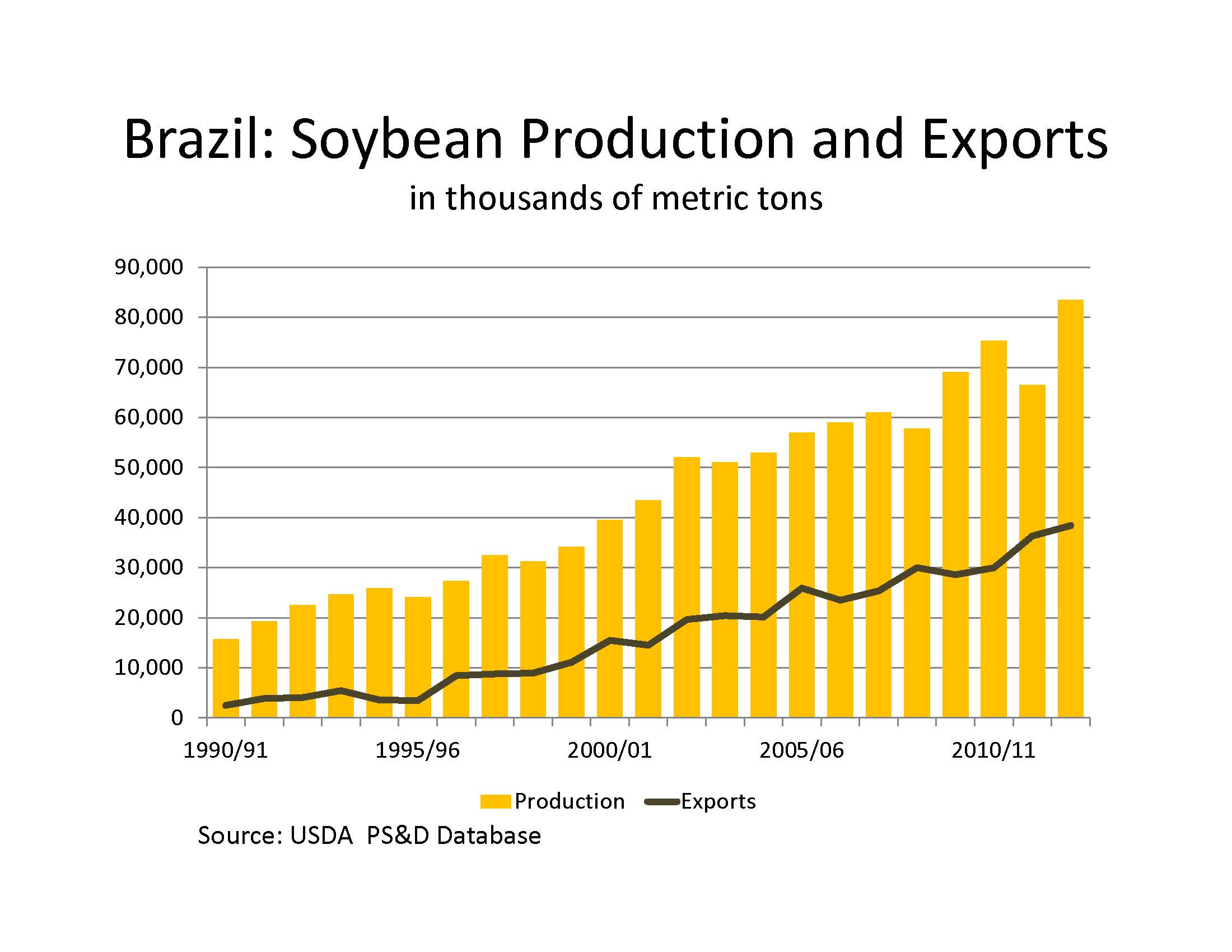

the potential for Brazil to become an agricultural powerhouse has long had analysts anticipating the country will surpass the United States in soybean production and exports – and 2013 may be the year those predictions come true. As of March, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) pegged Brazil’s 2012/13 crop at 83.5 million metric tonnes (mmt) compared to the 82.1 mmt US crop; and projected Brazil’s exports at 38.4 mmt compared to 36.6 mmt for the US.

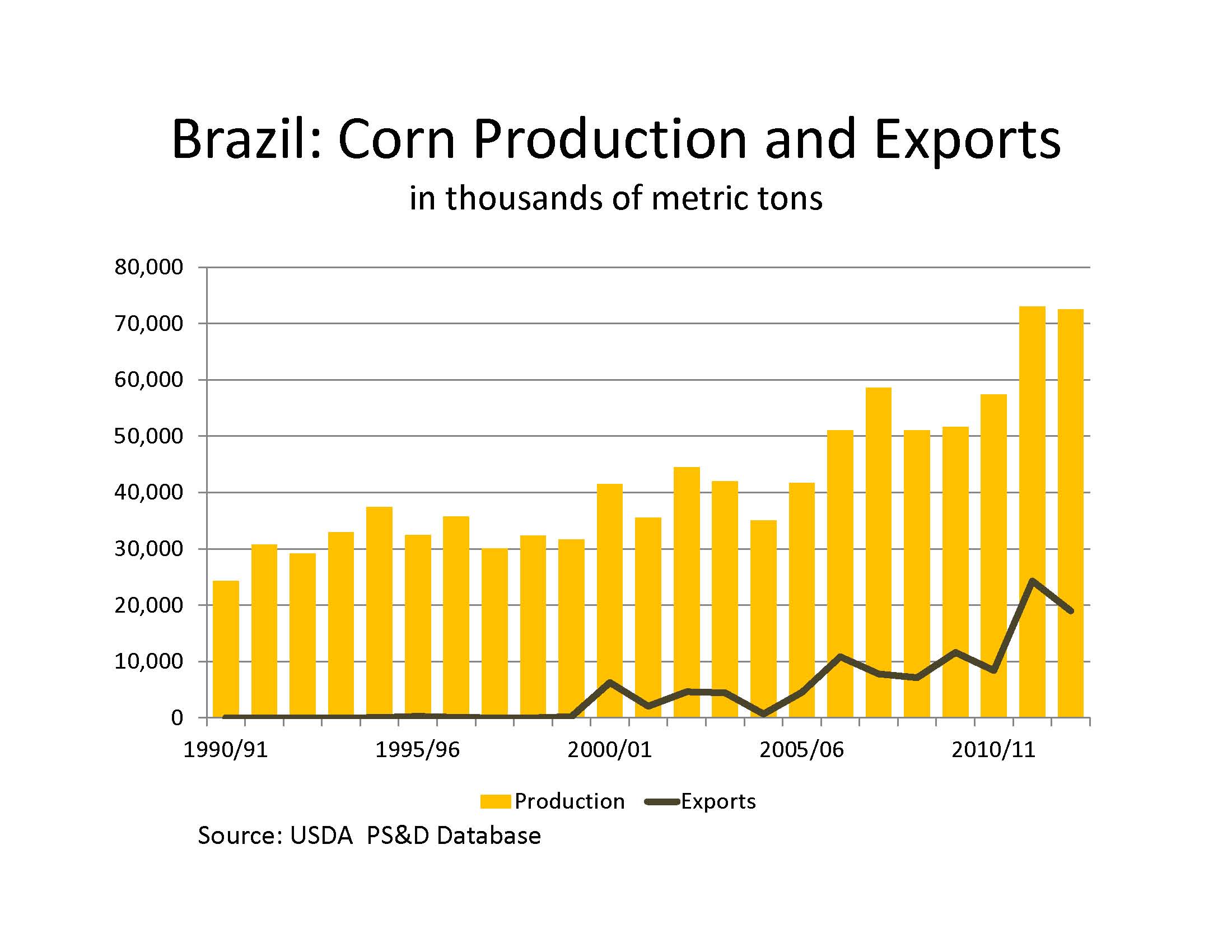

However, experts have also recognized how Brazil’s infrastructure limits its capacity to deliver, and in March, a combination of factors turned Brazil’s export boom into a logistical nightmare. In addition to a record soybean crop, Brazil has produced a large corn crop, most of which is bound for export. The result is corn exports have more than doubled compared to 2012, and soybean exports are expected to be six mmt higher than last year. Corn exports, normally completed in December, were still moving through the port system in late March. Meanwhile, a delayed soybean harvest is likely to compete with Brazil’s second mid-season corn harvest for space, further complicating the export scene. Finally, a new law limiting the number of hours a trucker can drive each day is reducing the flow of commodities from interior growing regions to export terminals. By March 25, a record 15-mile line of trucks was waiting to unload soybeans at Brazil’s busiest port, and 212 vessels were waiting for cargo.

Eight of 10 soybean shipments to China’s Shandong Chenxi Group failed over a two-month period, prompting Chenxi to consider redirecting orders to Argentina and cancelling some two mmt in purchases from Brazil.

“The infrastructure, which has always been below current needs…is now unsustainable in terms of flow capacity,” says Luis Neves, Director of Logistics, CHS in São Paulo, Brazil.

The shipping backlog isn’t likely to resolve quickly, according to Neves, who expects shipping pressures to be “intense” for three to four months. He puts the wait to load a ship at 35 days for the port of Santos and 55 days at Paranaguá, Brazil’s second largest port.

“Outside of Brazil’s farms, we’re no longer an agricultural powerhouse. The state of our infrastructure is a disaster,” says Nelson Piccoli, of the Mato Grosso Agricultural Federation.

Brazil’s government is well aware of the infrastructure challenge and is targeting roads, railroads, and new port development in the north to serve agricultural development in the Cerrado. The plans, however, have yet to ease farmers’ transportation problems.

For example, a thousand-mile road from Cuiabá to Santarem, promised since the 1970s, still has 600 miles of dirt surface that can take 30 days to drive. The cost to truck soybeans from the Mato Grosso region to a port has jumped 56% this year to $152 (US) per tonne. That reduces Brazilian farmers’ profit margins to roughly a third of what US farmers earn, despite 30 percent higher yields.

The world leader in soybean production, Brazil is also a growing force in corn production. In 2012-13, it will produce 72.5 mmt of corn, making it the world’s third largest producer, behind only China and the US and followed by the European Union, according to USDA projections. Argentina is expected to come in sixth, behind the former Soviet Union.

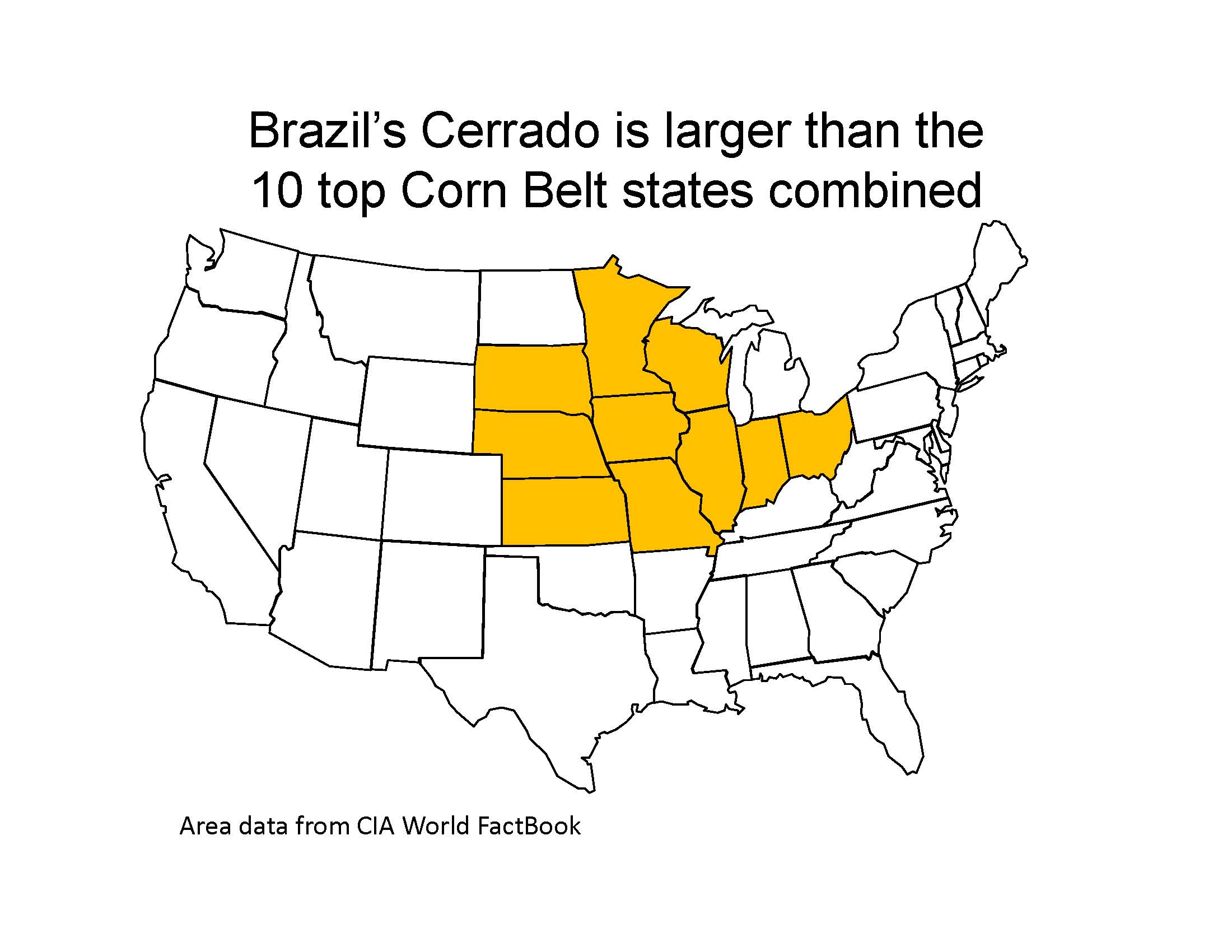

Corn is mostly grown in Mato Grosso or Parana as a second-season crop or the preferred rotational crop for soybeans. In the Cerrado, a relatively undeveloped region larger than the top ten US corn-producing states, only 25 million acres out of 500 million were planted to corn in 2011/12.

At present, infrastructure limits Brazil’s ability to move corn through its port system and into international markets, especially since the incentives to export soybeans are much stronger. As a result, storage and transportation resources typically go to the soybean sector, at the expense of Brazil’s corn economy. Other challenges facing Brazil’s corn sector include the need for genetics better suited to the Cerrado’s weather, higher production costs, and storage conditions associated with Brazil’s climate.

Still, industry analysts note that Brazil has more untapped arable land that could be brought into production than any other nation in the world and that high world corn prices will motivate Brazilians to expand production. •