The consequences of new technology

MORE TRAINING NEEDED

DIGITAL DATA-GATHERING technologies in agriculture, often referred to as precision agriculture, are becoming widely used across Ontario farms to monitor crop yields and they can have significant benefits when used to their full potential.

But, how are farmers adapting these technologies and what are the potential social consequences of their use?

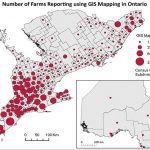

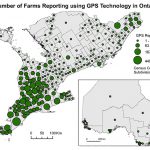

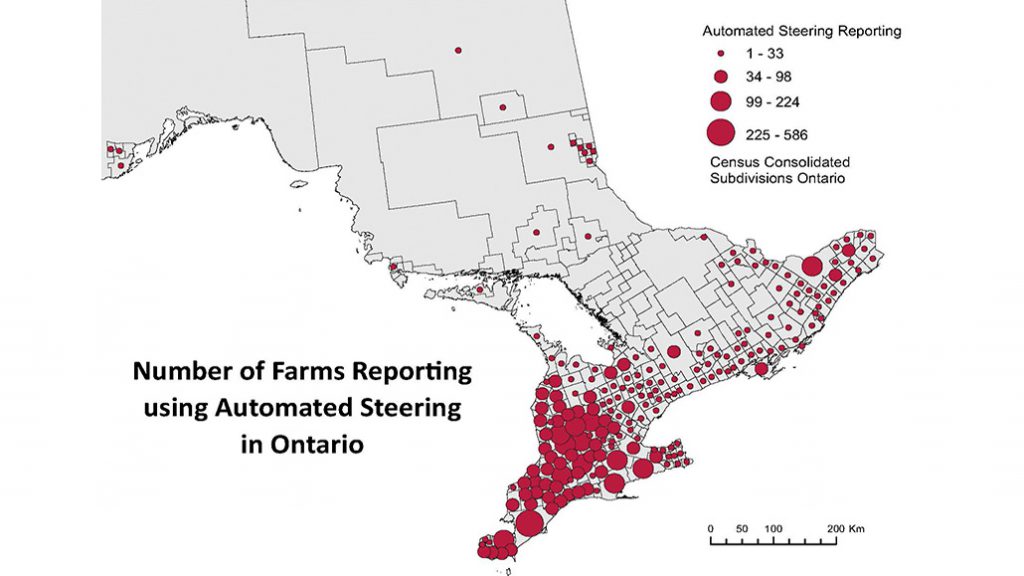

At the University of Guelph’s Department of Geography, PhD student Emily Duncan worked to analyze these questions and developed maps illustrating adoption of these farm technologies in Ontario.

Duncan’s research revealed that while adoption rates for precision agriculture in corn and soybean production have increased, not all growers are using precision agriculture technologies to their full potential.

KNOWLEDGE GAP

From interviews with grain farmers, dairy farmers, and precision agriculture technology retailers she found potential social consequences of digital data-gathering technologies in agriculture. For example, she found retailers are having a hard time hiring people with an understanding of the technologies.

Because of this gap in knowledge, farmers are finding it difficult to learn about these new tools.

“Digital data-gathering technologies are the future of agriculture, we’re moving into this digital era, but we don’t want Ontario to fall behind because we haven’t developed programs to adequately train people,” says Duncan. “We need a stronger focus on training the next generation of people in agriculture to increase understanding of new technologies and data management.”

Improving utilization of these technologies in Ontario is important for increasing grain production and sustainability of farming. The precision agriculture technologies investigated included automated steering of tractors and geographic information systems (GIS) mapping which generate maps illustrating yield produced per hectare. Even with access to these technologies, many farmers do not know how to use the data to improve measures such as crop yield or fertilizer use.

Duncan’s research strongly recommends that institutions such as universities, colleges, and the province work together to better educate Ontario’s agricultural community in new technologies.

Precision agriculture can benefit farmers by increasing crop yield while simultaneously reducing production costs. Farmers’ access to this information is limited to the machine it was gathered on because, in some cases, they don’t own the data collected.

NEW CAPITAL

Recently, data has been referred to as a new form of capital, and it has value to it, says Duncan. This has created growing concerns among farmers with ownership of data collected by precision agriculture. These farmers pay for the technologies that collect data, but in some cases the companies benefit from this new form of capital.

“We need to start thinking about the power relations and power imbalances with these technologies,” says Duncan.

She says the ownership of this data is being questioned by farmers and researchers. Some farmers feel that they should be compensated if corporations are going to be using the data that their farm technologies are generating.

In the future, Duncan wants to look deeper into the social consequences of these new technologies. She hopes to generate a greater understanding of how technology is changing farming and possibly most importantly, how data collected from precision agriculture can benefit farmers.

This research was funded by the Canada Research Chairs program and by the Canada First Research Excellence Fund’s Food From Thought initiative. •

SPARK (Students Promoting Awareness of Research Knowledge) is located at the University of Guelph’s Office of Research. For more information, contact SPARK at 519-824-4120, ext. 52667.