Democratization of data

GRAIN ANALYSIS AND PRECISION TECHNOLOGIES

THE SHEER EXPENSE of precision and crop-analysis technologies has long been cited as a major barrier to farmer adoption. Many new developments, however, are trending less towards the proprietary model and more towards adaptability.

For farmers, this means increasing the opportunity to adopt effective aftermarket data tools — and at comparatively lower costs.

MORE EFFECTIVE INDEPENDENT SYSTEMS

According to John Sulik, professor and technology researcher in the University of Guelph’s Department of Plant Agriculture, getting flexible and more useable technology to more farmers is increasingly easier thanks, in part, to rapid advances and cost reductions in GPS. This has allowed some companies to find ways around traditionally expensive and enclosed proprietary systems.

| TERM DEFINITION GPS: Global positioning system – The original satellite-based navigation system first developed by the United States military and released to the public in the late 20th century. GNSS: Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) – This is similar to GPS, but with a wider net of available satellites. RTK: Real-Time Kinematic – This is currently the most accurate form of positioning system. Signals are received via in-cab equipment, as well as a ground station, allowing for real-time corrections. |

For example, technologies such as the GNSS module ZED F9P — a dual-frequency positioning system developed by a company called u-blox — can be purchased and applied as an alternative to paying RTK unlocking fees on some equipment.

In Sulik’s case, that refers to drones. More specifically, he is currently conducting trials to see if the ZED F9P can successfully replace systems in his drone hardware. This comes after an experience where, once a drone had been purchased, a nearly equivalent fee was being charged to unlock its built-in GPS capability.

“The chip in the ZED F9P is incredibly affordable and it gives a position fix in under 30 seconds,” says Sulik.

More generally, he says the “tricky thing” about precision-ag technologies is

many continue to seem both promising and unproven.

“There are some clear-cut ones like section control and autosteer. If more people can access the basic technologies, I think it will be a tide that lifts all boats. Right now is the best time to start learning about GPS and incorporating it into your operation.”

GLOBAL COMMUNITY TAKING INITIATIVE

Sulik reiterates aftermarket-style systems are not adaptable — or perhaps even preferable — in every case. John Deere yield mapping and GPS technology, for example, only works within its own system, but that system does work well.

Tony Balkwill, an agronomist, researcher, and operator of NithField Advanced Agronomy, says the fact that control and monitoring systems have been heavily integrated into most new equipment means a lot of farmers continue being pushed into adopting proprietary systems. The main opportunity lies in the increasing number of lower-grade options, available for older equipment, driven by a growing global community.

“There are aftermarket things now, but not a lot of branding on it yet,” Balkwill says.

“It’s all just computer systems. People are starting to learn how to bypass things. If someone needs a combine to drive straight in Australia, someone in Saskatchewan does as well. There are some simple systems out there. Someone just has to work with a company.”

SUPPORT SYSTEMS CRITICAL

For Aaron Breimer, general manager of Veritas Farm Business Management, company partnerships are a main barrier to the democratization of more cost-effective and adaptable data technologies.

“Who is going to support you and what are you going to do with the deal? We’re closer on the support side but still trying to figure out the ‘so what?’ aspect,” says Breimer.

“So what?” is the central question Breimer asks of new technologies — that is, what actionable insights does the technology actually provide? If there is no support, in the form of data cleaning, for example, the effectiveness of the tool substantially diminishes. The problem is data support services can themselves be expensive and time consuming.

“Sure, you can have pretty maps just like the big operators, but just like them, you don’t know what to do with that,” he says.

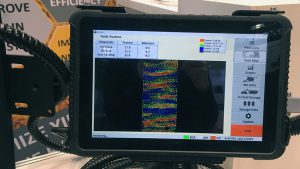

Breimer adds progress is being made in terms of establishing support partnerships for new technologies, with participation from both large manufacturers and smaller ag-retailers. Sylvite (formerly Thompsons), for example, has delved into data servicing and hardware sales for the relatively new FarmTRX retrofit yield monitor.

“John Deere has supported work in this space. It’s just not the go-to piece. When you get into that aftermarket it’s the people driving and requesting it,” he says.

Breimer also reiterates the importance of knowing what a digital tool is intended to accomplish, and whether the level of precision required matches its capability. For Veritas’ digital agronomy work, he says, millimetre-level precision is not always a necessity since accuracy is being derived from overlaying many data layers.

Conversely, some tasks do require more accurate — and thus more expensive — systems.

“Where unlocks are an issue are in things like doing your own field tiling. You need vertical and horizontal stability, and screwing that up is very bad. Good guidance in strip-till is also important,” says Breimer.

“If all you want to do is fleet management. Put an iPhone in the cab.” •