Alternative residue management

HURON COUNTY FARMERS GETTING GREAT RESULTS

A NEW SYSTEM for managing crop residue that doesn’t involve tillage is one of the most innovative advances in the 42 years Ian McDonald has been working in field crop research.

| WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW • Managing residue plays a major role in Lawrence Hogan and Steve Howard’s no-till success. • When planting soybeans after corn, they make sure the residue is in the right condition in the fall by evenly spreading it across the field. • They leave tall stalks — about 14 inches — to reduce residue matting. • This method also maintains cover on the land over winter, reducing water and wind erosion. • In the spring, they use a row clearer that pushes the residue back against the row of standing corn stalks to expose bare soil. |

“I’ve seen a lot of stuff in my time, but I’ve never been as excited as I have been with Lawrence and Steve’s work with biostrips and residue clearing in terms of making significant change in the system as a whole,” says the crop innovation specialist in the Field Crops Unit at the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs.

Lawrence Hogan and Steve Howard are brothers who have been no-till farming since the 1980s. They currently have 900 acres of corn, soybeans, and winter wheat in Huron County.

HOW IT WORKS

When they plan to plant soybeans after corn, they first make sure the residue is in the right condition in the fall. They use Calmer chopping rolls on the corn head and ensure the residue is spread evenly across the field.

“We find that soybean planting goes better after corn, and even that fall wheat planting goes better after soybeans because the corn stalk residue pieces are smaller,” says Hogan.

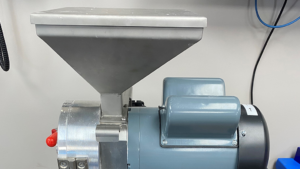

In the spring, they use a row clearer that pushes the residue back against rows of standing corn stalks, exposing a 14-inch strip of bare soil, which is where they plant twin-row soybeans.

“We’re not doing any tillage, and we use the row clearer two days ahead of planting, which means the soil gets dry enough to plant,” says Hogan. He adds that they don’t use this method on every field all the time — only when they feel it’s necessary when the soil is wetter than it should be, and there’s a potential for slug damage to the soybeans.

They plant twin-row soybeans using either a seed drill with 7 1/2 inch twins or a corn planter with 10-inch twins centred on

30 inches.

“We’re very happy with the row clearer,” says Hogan, adding that, at harvest, they strive to leave 14-inch corn stalks standing.

“We have always tried to keep the corn header as high as possible to leave tall stalks, which reduces residue matting that can happen with the Calmers rolls if the head cuts too low — it also helps the soil to dry in spring.”

The 16-row, 40-foot clearer was relatively inexpensive — about $32,000 three years ago. Hogan first bought an 8-row clearer in 2016 from Quebec after seeing it at the Outdoor Farm Show in Woodstock about eight or 10 years ago. The current clearer is pulled by a 90-horsepower tractor at half-throttle, so fuel consumption is minimal.

SYSTEM ADVANTAGES

The brothers have used this method for about five years for soybeans after corn. In the spring of 2020, they didn’t use the row clearer in any fields because the soil was dry. In some years, when soybean harvest was late and damp, they’ve also had to Phoenix harrow the remaining corn residue that was cleared in the spring to enable the soil to dry out ahead of wheat planting.

“You have to constantly pay attention to field conditions and be ready to change your plan,” Hogan says, noting that pretty much everything in farming can change on a dime, and they have to be prepared to rapidly adapt throughout the season to optimize the system.

Their soybean yields have consistently been above the county average and, in two out of the past five years, reached 70 bushels an acre.

Another advantage of the Hogan-Howard system is that it maintains cover on the land over the winter, reducing water and wind erosion. It also helps keep the soil healthy.

“We have to nurture the soil so it will nurture us,” says McDonald, pointing out that soil is a living ecosystem and that its physical, chemical, and biological needs must be met to stay productive.

He also says there’s a dynamic relationship between the art and science of farming.

“Science gives you the tools, and the art is in how you make the system function,” he says, adding that the goal for productive crops should be to optimize the system so that the most profit can be gleaned from the least inputs while protecting and enhancing the soil ecosystem.

While Hogan concedes the row clearing puts an extra step in the process for no-tillers, he says it’s been better than their past experience with traditional tillage, in which fields were worked in the fall and cultivated two or more or more times in the spring.

“Those three passes cost-wise would be at least six times more costly than running the row clearer once,” he says.

Another alternative to fall tillage for residue management or spring row clearing, according to McDonald, is a rapid, shallow till in the spring, when the days are warmer, and the residue is more brittle and oxidized from overwintering.

“Tillage was originally developed as a weed control system, and its use for seedbed preparation came later,” he says. “Now, we really don’t need a lot of tillage for seedbed preparation, but we can use it to manage the previous crop residue before planting the next crop.”

McDonald believes the row clearing system is a superior choice and that using this method supports no-till farming while resolving the challenge of managing substantial corn residue after harvest and the trash issues that often affect soybean early emergence and growth the next spring.

At the end of the day, he says, the system and the choices made should not be about bushels per acre but about dollars of profit per acre, with special attention paid to protecting and enhancing the soil platform.

As he summarized in an article in CropTalk, “This system is worth thinking about if your goal is lower costs, improved soil management and continuing to achieve top yields!” •