Biologicals

THE PROMISES AND PERILS

AS THE NEED to reduce carbon footprints grows, interest and investments in developing biological pesticides and fertilizers have exploded in recent years, but their effectiveness remains questionable.

“Large sums of money are being invested in biologicals … so it’s a great time to be curious and cautious,” says Dale Cowan in an on-demand presentation at the 2023 Ontario Agricultural Conference. “There are estimates that between $3.2 billion and $6.7 billion will be invested by 2027.” Cowan is an agronomy strategy manager and senior agronomist at AGRIS Co-operative.

BIG OPPORTUNITY

“The science and technology is changing rapidly, and there’s a lot of investment going into this space to better understand how these products work, how to make them better, and how to work with them to get a better success rate,” says Nathan Klages, biological business manager for Syngenta, in a presentation on Crop Day at the Grey-Bruce Farmers Week in January.

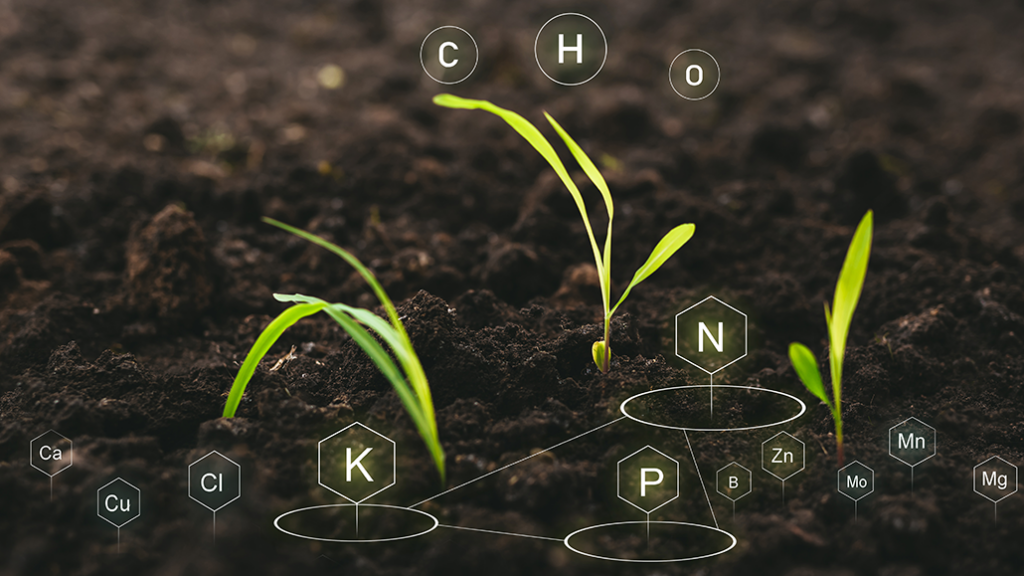

Klages outlined three basic categories of biologicals: biocontrols that address a specific issue involving insects, disease, and weeds; biostimulants that help crops better manage weather stresses like too much heat or cold; and biofertility like inoculants that use microbes to promote plant health and endophytes that live within crop plants and can fix nitrogen.

Klages explained that biocontrols are generally used more in fruit and vegetable crops. They are also getting some traction in row crops to avoid export market issues around residues from synthetics and fill in crop protection gaps.

“About 570 products are under review at the PMRA (Pest Management Review Agency) right now, and the reality is that some of those products won’t be available in five or 10 years, so we have to start thinking about what different kinds of products — synthetic and biological — will be needed down the road,” he says.

Cowan and Klages noted that 70 per cent of yield reduction in field crops is due to abiotic, or weather-related, stress, which biostimulants are designed to address.

Klages said that the biostimulant market is crowded, with more than 1,000 registered products aimed at improving crop quality and helping roots take up more of the nutrients available in the soil.

Growers, too, are enthusiastic. Klages showed the results of a study by Stratus Ag Research that showed that 29 per cent of growers said they planned to reduce their nitrogen fertilizer use in 2022, and 75 per cent said they were interested in trying a nitrogen-fixing biological on their farm.

WARNING SIGNS

“It’s important to be careful about product claims — and to ask what it’s supposed to do for the crop,” Klages says.

In summing up his presentation at the Ontario Agricultural Conference, Dr. Connor Sible of the University of Illinois said that while biologicals can be very beneficial for increasing crop yields, their effectiveness depends on the type of product, and he also warned producers to ask questions.

“You really have to ask the dealer, ‘what is it?’, ‘how does it work?’ and ‘is it something I really need, or can I save on those inputs and focus on something else?’” he said.

Cowan said that because his company is affiliated with Growmark, they have access to a program called Agvalidity that rigorously tests novel agricultural products for efficacy. A full 86 per cent of the products brought in for potential testing were rejected, and of the 302 products that were tested, only 12 have been approved.

DOWNSIDES AND ALTERNATIVES

At the same conference, Dr. Pedro Autunes from Algoma University warned growers that while one type of biological — arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi — is beneficial to plants, the inoculants that are currently commercially available do not work most of the time.

His advice was to “use management practices that promote indigenous mycorrhizal communities,” adding that more research is needed and that the industry is “decades away from” developing inoculants that do work.

In fact, in a paper he co-authored with other Canadian and Australian researchers, the findings around fungal inoculants were even more disturbing, given that no one knows the unintended consequences of the products. The paper entitled “Fungal inoculants in the field: Is the reward greater than the risk?” said that if the consequences include the fact that they’re invasive, “they may pose a threat to soil and plant biodiversity and ecosystem functioning.”

Similarly, Dr. Kari Dunfield, a professor in the University of Guelph’s School of Environmental Studies and the Canada Research Chair in the Environmental Microbiology of Agro-ecosystems, has been researching ways producers can reduce the use of chemical inputs and encourage the existing microbiome.

In a paper she and her team published, they showed that soil science, plant biology and microbiology have to be examined together because of the complexity of the environment.

It is called “It takes three to tango — the importance of microbes, host plant, and soil management to elucidate manipulation strategies for the plant microbiome,” and it was published in the Canadian Journal of Microbiology in May 2020.

It pointed out that inconsistencies in the effectiveness of commercially available biologicals stems from focusing on a single strain of the micro-organism, which is isolated and tested in a laboratory or greenhouse but often fails when put into field conditions.

It also said that while work is being done in plant breeding to develop varieties that encourage healthier microbiomes and greater resistance to weather, pests, and diseases, it’s a long and laborious process.

In the shorter term, Dunfield’s research is focusing on using genomics to discover how management practices like introducing more crop diversity and reducing the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides positively affect the microbiome. •