Order of Canada

SOYBEAN BREEDING PIONEER RECOGNIZED

THIS FALL AT Rideau Hall, when Governor General Julie Payette calls on Canadian crop breeding icon Dr. Harvey Voldeng to come forward and accept his Order of Canada officer award, applause will ring out from coast to coast.

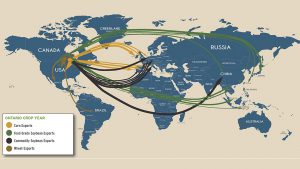

Voldeng, a now-retired Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) plant breeding program director, is widely credited with having developed cold-tolerant, food-grade soybean varieties — most notably, Maple Arrow, in the 1970s — that were game-changers for what is now a $2.8-billion industry.

Voldeng’s varieties gave Canadian farmers new cropping opportunities and helped progressively minded seed companies such as First Line Seeds get a foothold in export markets. Company founder Peter Hannam of Guelph, who in 1961 was famously told by his Ontario Agricultural College crop science professor that soybeans would never grow north of London, calls Voldeng’s contributions “the foundation.”

“His Maple Arrow variety was the first really good cold-tolerant soybean variety from public breeding in Canada. He’s had a wide impact,” says Hannam.

LASTING IMPACT

Voldeng’s award, along with 20 others named an Officer of the Order of Canada, was announced in June. His citation succinctly reads “For his innovative research on soybean cultivars and for his substantial contributions to Canadian agriculture and the economy.”

Indeed, there’s no question soybeans are making a huge difference to agriculture’s bottom line — and to the GDP of our nation. New variety development helped soybean production grow by 103 per cent from 2009 to 2018. Planting hit 3.1 million acres in Ontario this year, a three per cent jump over 2018, which was also a record year. And while soybean acreage is down in comparatively cool Manitoba this year, farmers there still planted more than 1.5 million acres of soybeans.

That kind of acreage is a sea change from the early 1970s, when plant breeder Voldeng, a native of Spalding, Sask., was eyeing fields around Ottawa’s Central Experimental Farm where he was stationed — and there wasn’t a soybean in sight.

“I could drive for 45 minutes and still not see any soybean fields,” he recalls.

But the desire to grow them — or at least something like them — was there. As current Ottawa soybean breeding program director Elroy Cober says, Voldeng had his ear to the ground. He’d taken the pulse of eastern Ontario growers, and knew there was an appetite for profitable, sustainable protein options to rotate with corn.

Soybeans, with their innate ability to fix nitrogen, fit the bill…if only they could tolerate the cold.

Like Hannam, though, he wasn’t satisfied with conventional wisdom about soybeans’ hardiness. He believed that introducing cold-tolerant genetics into conventional soybean varieties could render an early maturing soybean variety that could grow in non-traditional production regions…like those around Ottawa, where his efforts were primarily focussed.

“I had faith in their ability,” Voldeng says. “Soybeans are tough little plants.”

And maybe nowhere are soybean plants tougher than in chilly Scandinavia, where through the 1950s and early 1960s Swedish breeders worked with soybean genetics from Russia and Japan to further their own cold tolerant varieties.

Voldeng turned to these genetics to incorporate into his own breeding program. He worked with industry leaders in Ontario such as Hannam and University of Guelph plant scientists Dave Hume, Wally Beversdorf, and Jack Tanner and their graduate students — including Cober — developing and field testing varieties that would succeed in 2500-2700 CHU zones.

Ultimately, the marriage of Scandinavian and Canadian genetics yielded Maple Arrow. The first part of the name is situational, coming from a roadway associated with the experimental farm named Maple Drive, and gave the variety some geographic context. The second part of Maple Arrow’s name was inspirational and symbolic.

“A soybean plant in the field with good pods at the top looks like an arrow, pointing straight up, pointing to the future,” says Voldeng.

VARIETIES

Other varieties that evolved from the Maple line are also well known to Canadian growers. Among them are Maple Glen, developed by Voldeng and Cober and released in 1987 as a food grade soybean variety. More than 1.2 million acres of Maple Glen were grown through the late 1980s and 1990s, later earning it the title of Seed of the Year, an award bestowed by SeCan and the University of Guelph.

Voldeng was also a pioneer in developing soybean varieties for natto that were highly desired in Japan — “we put a lot of effort into developing a small seed,” he recalls — and the high-protein varieties roasted for dairy herds’ consumption in eastern Ontario and Quebec. The difference in such varieties is profound and underlines a soybean’s versatility…along with underscoring Voldeng’s mantra about maintaining a wide genetic base through the species.

“If you narrow the germplasm base too much you can affect yield,” he says. “Maybe that’s not too serious of a problem now, but it’s something to keep in mind.”

And giving thought to new soybean varieties may be more of an imperative than ever, with plant-based diets becoming all the rage, at least in some circles. Diversity is a key right now — at one time, it was non-GMO varieties that had the spotlight with consumers. But with the overall drive towards meat-protein replacements, genetic modification may be less important than volume, to ensure processors have adequate plant-based protein to meet demand.

Voldeng ponders these and other matters, admiring how breeding has moved ahead with technology, even though he believes conventional approaches still have a role to play in soybean breeding.

“In some cases, for traits you can see easily, it may not be necessary to develop a GMO variety,” he says, noting that more hidden traits, such as fatty acid profiles, may require a different approach.

After a full and fascinating career in research — one in which he watched changes occur that he had a hand in creating — Voldeng was nonetheless floored to be nominated for the Order of Canada.

“I had no idea that I was being considered, but I’m very pleased,” he says. “It’s a recognition that I’ve worked with some good people.”

Adds Cober: “It’s a big compliment to Harvey, who so willingly shares his expertise, and it’s very gratifying to us all when a federal scientist is recognized with an Order of Canada award for his contributions.” •