How fields dry

AND WHY THEY CAN BE SLOW TO DRY

This article is a supplement to the Water Management series article ‘A second look at farm drainage’ that appears in the January issue of the Ontario Grain Farmer magazine print edition. It is a case study written by the authors based on spring 2017 field and weather conditions.

Wet spring weather during the spring can be frustrating to the Nth degree! Fields can take a long time to dry out during persistent rainfall (even when it isn’t above normal rainfall); and you might be wondering why.

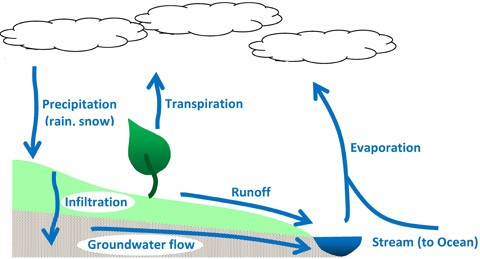

There are two primary factors, one above ground and the other below. Fields can dry by one of two means. Moisture can either evaporate or transpire into the atmosphere from the soil surface or through plants, into the atmosphere above ground. Below ground, water leaks out the bottom through to the water table in natural systems, or into the tile drainage system in many agricultural fields (Figure 1).

There are many contributing factors in both cases.

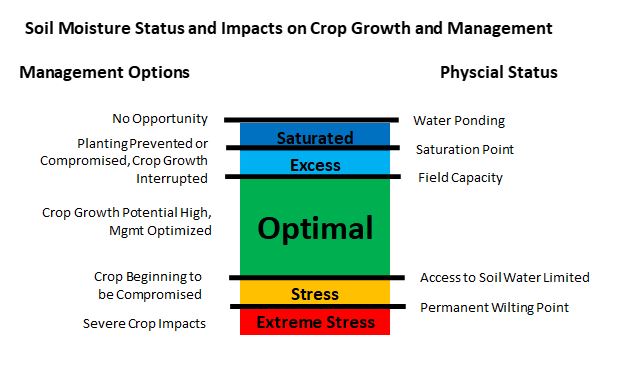

Below ground, the amount of rainfall has been rather high across much of the province earlier (less volume lately, just mostly small persistent rains) and the entire system is full as noted by high water levels in the Great Lakes and flooding along many rivers. When the system is full, there is nowhere for water to flow in the upper reaches of the watersheds, so the moisture just sits until the system begins to clear out at the distal end. So, we have saturated fields with nowhere for the water to go below ground. While damp fields are the norm currently, consider how every season somewhere we have the opposite problem. How water is distributed within the soil profile impacts all aspects of crop establishment and growth. Figure 2 highlights the impact of different levels of soil moisture on crop growth and development and field operations.

The other thing below ground to consider is the past and current management of fields. We have talked for the last few years about the loss of soil health across Ontario’s farm country. This “sealing” of the soil through soil compaction, loss of organic matter, and excessive tillage all contribute to the system being exacerbated this spring. This leads to lack of infiltration into the soil, which leads to ponding and otherwise saturated soils near the surface. This coupled with the “full” system helps to explain part of the problem.

This below ground issue is further burdened by what is happening above ground. The evaporation and transpiration routes to water removal from the soil into the atmosphere has been severely reduced this spring because of the cool, humid, low wind, cloudy days. Moisture removed from the soil surface and drawing upwards on soil water is slowed down when we have this type of weather. We are missing the “Drying Power of the Atmosphere” this spring. For evaporation to occur, there must be water available at or near the surface (no shortage of that right now), energy to get the water molecules moving (mainly sunlight) and space in the atmosphere for the water molecules to go. So, given the damp, cool, and cloudy conditions this spring, few of these requirements are being met.

The lack on sunlight and temperature has reduced thermal differences above the soil surface and has prevented the climate gradients that occur with bright warm conditions, not providing enough energy to drive evaporation. To dry out soil we require warm, bright weather which reduces humidity (warmer air is less dense and can therefore hold more water vapour) and generates wind. This combination is what “wicks“ water off the soil surface.

Further contributing to this problem this time of year is a great deal of crop-free fields. Without plants to transpire, water removal from the soil is further compromised. As there is no real vegetation growth at this point, there is not really any transpiration occurring, leaving evaporation as the main above ground drying process. Even if the crop was planted, the cool, cloudy conditions would be stifling growth and thus the rate of transpiration.

While it will turn around at some point soon, it points out how susceptible we potentially are to climate change, where climate change impact on agriculture (and elsewhere) is not so much increasing overall global temperatures, but the unpredictability of weather patterns. Under the types of conditions, we have experienced this spring, there is not a darn thing management wise we can do that would get us on the fields any earlier. This is a bit of a stretch. Some things we can do is build soil health that allows the system to hold more water but have the resilience to carry equipment on this higher total water volume scenario. This also helps in seasons when we need a bigger “bank” in the system to provide water to our thirsty crops at critical times during the growing season.

Work by Dr. Jerry Hatfield at USDA-ARS and colleges at Ames Iowa is modelling weather and not being thrilled with what they are finding. Observations from these investigations to date would suggest increasingly wet falls and springs, coupled with overly dry summer periods. This is not a recipe for high productivity crop agriculture. Mudding the crop out of the fields during fall harvest and similarly mudding it in during the spring planting season does not set a crop up to perform under the best summer conditions, and much less so under low rainfall summer growth periods.

We will have to understand better how to manage cropping if this layout of seasonal weather continues to occur in future.

Ian McDonald is the crop innovation specialist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA). Dr. Richard Petrone and Dr. Merrin Macrae are professors within the Department of Geography and Environmental Management at the University of Waterloo.