Harvesting data

KNOWING WHAT TO KEEP FROM THE FIELD

COLLECTING ACCURATE HARVEST data begins in the spring. That’s when you get your first indication of how a crop is performing.

“What you see in the spring is what you will see in the fall,” says Jeremy Visser, research technician at Maizex Seeds. “It’s easier to see what’s happening when you are taller than the corn. You want to look for uniformity and identify spots that show variability. Once the crop falls behind in the spring, you will see a correlation to your harvest results in the fall.”

Visser, who has 13 years of experience conducting field crop research, says it’s important to know the history of your field and the traditionally poor performing spots when you are planning to conduct any sort of on-farm trial to test out a new crop input or hybrid.

Visser and his team at Maizex utilize farmer cooperators to conduct some of the hundreds of strip trials they do every year on their hybrids against competitors. Farmers are given five to 10 different hybrids to see how well they perform on their farm. This allows farmers to try out new hybrids in their field and provides real-farm results for Visser to assess how suitable they are for growing in a particular region.

Sometimes, as the strip trials are assessed, he has to make the decision to discard part of the trial due to the obvious interference of external factors not intended to be part of the research.

“We have one field this year where the front 500 feet is highly variable. It was tiled and a laneway used to be there. So the suggestion I am going to give is to discard the first 500 feet of the field and not include that data in our final results,” says Visser, adding that no data is better than bad data when it comes to informing your crop decisions.

EQUIPMENT PREP

That’s why it’s also important to ensure that your data collection equipment is properly calibrated before the start of harvest to ensure your results are reliable. Visser recommends that you calibrate your weigh scales and your moisture meters and confirm they are within an allowable tolerance by comparing your results to a test done at a local elevator. A one percentage point error is acceptable for most moisture meters.

In addition to moisture level and test weight, farmers are most likely to collect and evaluate yield data. Visser says they collect this information as well as disease tolerance, dry down, stay green, and various other traits on the thousands of different hybrids they test in their research program.

Farmers who are experimenting with a new input, such as a fungicide, or new hybrids, should try to be as consistent as possible when collecting data from their trials. They should collect data on the same day, from the middle of the plot, and if possible, conduct a blind assessment without reference to the specific application or hybrid that was used so that they won’t be tempted to score it differently based on any bias they may have.

One way to collect the data without bias is to assign a unique number to each plot within a trial. This is also important to ensure that the data collected stays referenced to the correct plot within your database.

A way that Visser checks for consistency after collecting his data is through a statistical test known as coefficient of variation (CV). CV is a measure of relative variability. It is the ratio of the standard deviation to the average. Your variation across a field should be within a certain percentage and you shouldn’t be able to detect a pattern which would indicate an external variable (such as compaction or improper application of a fertilizer) has interfered with your plot.

It’s important to note that statistics are only meaningful if enough data points are available and verified — that’s why replications of trials are conducted by field technicians.

VARIABILITY

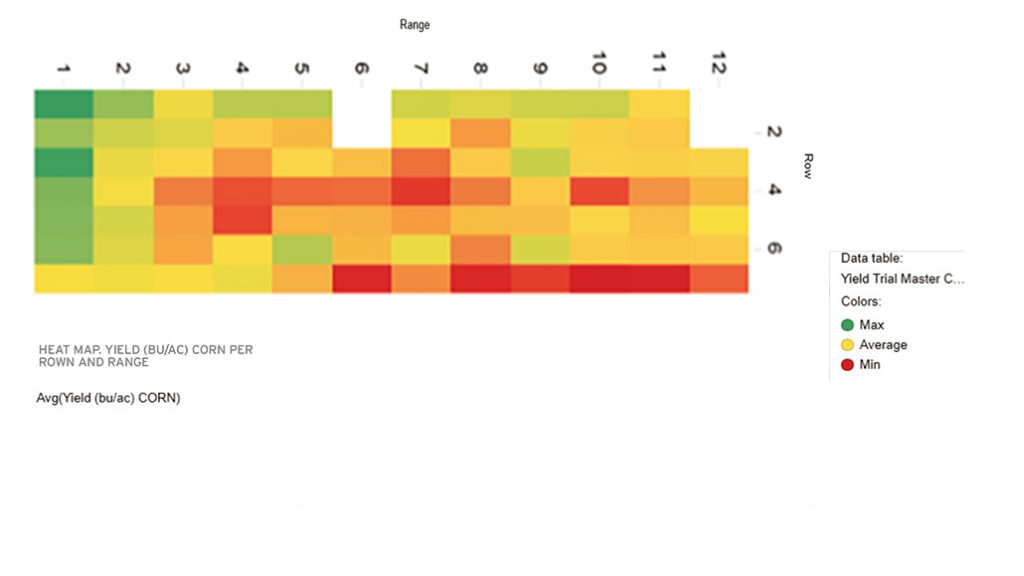

Creating a heat map with his data is one way Visser is able to visualize variability and look for patterns which indicate data that should be thrown out. He is able to create these maps because Maizex plants its field trials in a grid formation which easily allow for uniformity. Farmers who plant strip trials would get a similar representation of variability with the yield map generated by their monitoring system.

Visser says it doesn’t matter what system you have for collecting data, whether that’s a factory provided system on your combine or one you’ve added on after market, as long as it is calibrated properly and allows you to collect the information that you want. Similarly, it doesn’t matter if you are storing your data in an Excel spreadsheet, Access database, or a professional software system as long as you can maintain the accuracy of your information when transferring it from one place to the next.

Maizex uses its research to ensure the products it is selling are the best options for farmers; however, Visser suggests that there is nothing wrong with farmers doing their own homework and figuring out which systems work best for them given their own soil types and management styles. One size does not fit all when it comes to farming.

Visser reiterates it’s important to test out something new on a small scale before jumping in and applying it full scale. And farmers shouldn’t be afraid to throw out the information from a trial if something looks questionable.

This article is part of series which highlights lessons from the 2018 Technician Training Workshop which may benefit farmer-members involved with on-farm research or those interested in doing some of their own field experiments. Go to www.ontariograinfarmer.ca to review all articles in the series.

The 2018 Technician Training Workshop was sponsored by C&M Seeds, Cribit Seeds, Dow AgroSciences, Grain Farmers of Ontario, Horizon Seeds, Maizex Seeds, Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, SeCan, and the University of Guelph. •